2. The changing world of work: what does this mean for PES?

- Contents

- 2.1 What are the emerging trends in the future of work and what are the implications for PES?

- 2.1.1 What does a global labour market mean? Global enterprises

- 2.1.2 How have digital and technological advances impacted on the labour market? Changing types of labour, new skills, new sectors and new forms of work

- 2.1.3 What does changing demographics mean for worker profiles?

- 2.1.4 What does climate change mean for the labour market and PES services?

- 2.2 What does the future world of work mean for PES?

- 2.2.1 What will the role of PES be? A coordinating role

- 2.2.2 How can strategic and delivery partnerships for employment be built?

- 2.2.3 How can core services be updated and why?

- 2.2.4 What can PES offer around career guidance and lifelong learning support?

- 2.2.5 What are labour market information systems and how can these be used in relation to services for jobseekers?

The world of work is rapidly evolving and what is understood as ‘work’ is also changing as a result of different technological, demographic and climate change trends. The concept of ‘a job for life’ is diminishing and more varied career pathways are emerging. This means that PES need to update and adjust their service offer so that they can best serve enterprises and jobseekers within today and tomorrow’s labour market. By future proofing their services and becoming agile organisations, PES will be able to adapt more quickly to emerging needs and help their staff to become empowered to make informed decisions that best serve the individual needs of jobseekers and enterprises.

PES have traditionally served the primary role of matching unemployed jobseekers with enterprise vacancies. Face-to-face support by frontline counsellors played an important part in registering jobseekers, providing them with job search assistance and placing them into suitable employment. PES provided active labour market programmes (ALMPs) to provide training or employment opportunities to certain target groups, but they did provide wider career guidance or lifelong learning support. Internally, PES in the past often had rigid management systems and their IT systems may not have collated expansive, user-friendly data sets. In combination with other factors such as rigid management structures, these aspects may not allow PES to rapidly react to emerging needs of the labour market. The ILO calls for a human centred approach to delivering the future of work via three pillars, demonstrated in Figure 2.1 below. PES have a central role delivering this vision however they must evolve to meet the emerging trends and ‘futureproof’ their services.

This section will provide an overview of the emerging trends, the implications and opportunities that are subsequently created for PES.

Figure 2.1 Delivering the social contract – the ILO’s human centred approach to the future of work1

2.1 What are the emerging trends in the future of work and what are the implications for PES?

The world has changed significantly in last 30 years following rapid technological developments, globalisation and demographic changes. The introduction and mainstream access to the Internet has led to the rise of online, digitalisation services as well as providing individuals with the ability to work anywhere in new emerging, atypical employment. Technological developments have also contributed to the emergence of new sectors on the one hand and, on the other hand, the demise of other previously dominant sectors. The latter has also been impacted by the growth of globalisation, for example transnational companies can maximise the benefits of the global labour market. It is also worth noting that demographic trends, such as greying populations and the rise of a young, mobile, migrant population in certain countries, have implications on national, regional and local labour markets and the types of support services that will be needed by PES.

The following pages look at the emerging trends in the world of work in more detail and the implications for PES and workers.

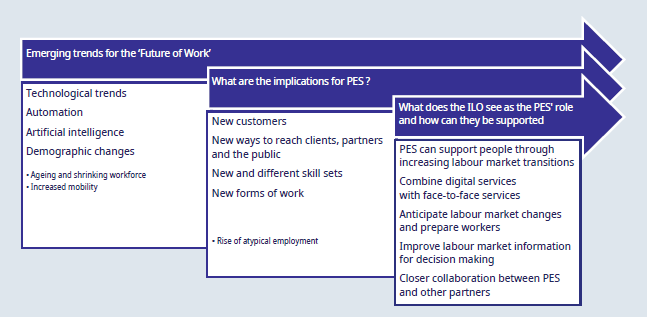

Figure 2.2 Emerging trends, implications and possible actions by PES2

2.1.1 What does a global labour market mean? Global enterprises

Globalisation has led to a global labour market where large, transnational companies can be located in different locations across the globe, working across national boundaries. This is more prevalent in certain sectors, such as manufacturing, where companies can move relatively freely so that they are located close to skilled, cheap labour force. This means that some workers can be affected by companies re-locating as their skill sets are no longer required by enterprises in the local, regional or national labour market and this means that workers need to upskill or reskill.

Within this, PES have a role to support workers in adjusting to such changes. This can include working with enterprises where redundancies are being made to provide information, guidance and assistance to at-risk workers to help them make work-to-work transitions within the labour market as well as providing workers with, or signposting workers to, opportunities to reskill and upskill according to the needs of the local and regional labour markets.

2.1.2 How have digital and technological advances impacted on the labour market? Changing types of labour, new skills, new sectors and new forms of work

The digital revolution and wider technological developments have impacted on the labour market in three main ways:

- Changing the types of labour required by the labour market;

- Requiring new skills by workers; and

- Introducing new platforms for work and atypical forms of employment.

2.1.2.1 Automation

Production and manufacturing tasks are increasingly automated as technological developments allow for certain tasks to be undertaken by robots. Such investments in automated processes can lead to greater efficiency of tasks and greater profit margins for enterprises. Technology can free workers from arduous labour, from dirt, drudgery, danger and deprivation and it can reduce work stress and the risk of potential injuries in the workplace. This is particularly prevalent in certain sectors such as manufacturing, construction and agriculture3.

In comparison, other types of work that require personal services (such as care services) as well as those that require analytical, high-level jobs are not touched by automation and this can lead to polarisation in the labour market.

This means that some workers can become displaced as their skill sets are no longer required, and others may need to upskill so they can be retained by their enterprises in a new role. The introduction of technology in the workplace may also lead to a decline in worker satisfaction as their responsibilities and activities change. The ILO4

calls on a ‘human in command’ approach to technology in the workplace so that ultimate decisions are made by humans, not algorithms. The availability of data can provide new, interesting insights and knowledge bases; however, there are implications for workers’ privacy. The ILO recommends that enterprises, workers’ organisations and governments monitor the impact of new technology in the workplace to ensure that workers can be protected.

2.1.2.2 New skills required by workers

Increasingly workers are required to have greater IT and digital skills so that they can adapt to labour market needs and work with the automated approaches. It is not just new skills but also the emergence of new roles that are introduced to manage, monitor and facilitate the automated processes. Workers need to upskill or reskill to keep pace with technology developments as well as the requirements of the labour market. PES therefore, have an important role in working with enterprises to upskill and reskill their employees as well as signposting jobseekers to further training and supporting workers through transitions from unemployment-to-work as well as work-to-work transitions.

2.1.2.3 Emerging atypical employment and new platforms for work

In the last decade there has been a sharp rise in new types of work and atypical forms of employment. Non-standard employment has led to a fl exible workforce with a rise in part-time employment and a rise in the use of temporary contracts. This includes the use of ‘zero hour’ contracts where enterprises do not state the number of hours required per employee and thus do not provide workers with the security of a set number of hours of work per week, or month. Such moves have led to an ‘on demand’ workforce that can be utilised as and when enterprises need labour. While this has benefits for enterprises it also makes employment much more precarious and less secure for employees.

The emergence of online platforms has created opportunities for individuals to work as they want and where and when they want. The ‘gig economy’ allows workers to shape their work and working hours as they wish, for example carving out a career via mixing different short-term, part-time employment or undertaking short-term tasks around other full-time employment opportunities.

Micro-task platforms and smartphone apps allow workers to do smaller tasks and they can help organisations to have simple tasks undertaken by qualified individuals anywhere in the world. They can also help organisations to collect data on mass over large geographic areas much more easily. The ILO6 c alls on policy makers and labour market institutions to recognise the gig economy as a new form of work and to make steps to ensure workers protection. This means that in the future PES could recommend the gig economy as a viable route to employment.

Another new emerging form of work is crowd-working7. This is a ‘new’ type of work that has emerged from advances in the access to the Internet and IT improvements. It allows enterprises to access workers across the world to do specific tasks, ranging from computer programming and data analysis to ‘microtasks’ like data entry. Workers can be based anywhere and only need an Internet connection. Enterprises have no obligation to hire workers, sign contracts or meet labour laws. Workers have little say over when they work, working conditions or unfair treatment.

Box 2. Non-standard forms of employment8

There are four broad types of non-standard employment:

1. Temporary employment- Workers are employed for a specific period, including fixed-term or project-based contracts.

- Covers casual work, where workers are used for a very short-term basis, occasional or intermittent basis.

Examples: seasonal work or casual work.

2. Part time work

- Normal working hours are fewer than those of comparable full-time workers.

- In some cases, working arrangements may be few hours or no predictable hours.

Examples: ‘zero-hours contracts’ or ‘on-call’ work.

3. Temporary agency work, and other forms of employment involving multiple agencies

- Workers are not directly employed by the company to which they provide services, but they are paid and deployed by an agency.

- Often a contract will exist between the enterprise and agency and agency and worker.

Example: temporary agency workers.

4. Disguised employment relations and dependent self-employment

- Workers may appear to be self-employed, but they are dependent on the enterprise.

- In some cases, enterprises may monitor activity, which does not comply with the worker’s independent status.

Example: enterprises may hire workers via a third party or engaging them in a contract that is not an employment contract.

2.1.3 What does changing demographics mean for worker profiles?

Across the globe different countries have witnessed changes to their demographic profiles and this has implications for the working age population. Many countries have a lower birth rate than in the past, coupled with an ageing population with the average life expectancy for men and women increasing. This means that there is a greater pressure on the working population than in the past, as there are greater strains on health care and other services that are required to support an older population. This is often referred to as the ‘dependency rate.’ This means that the retirement age is being extended, or is the subject of extensive discussions, across the world.

In terms of the working population, this means that they are likely to need to work for longer and beyond the (current) official retirement age to support themselves throughout their lives. In addition, older

workers will be required to upskill or reskill so that they can prolong their careers and adapt to advances in technology and the wider needs of the labour market. In comparison, younger workers (or young people who will enter the workforce in the future) will need to diversify their skill set during their careers and they will need to be engaged in lifelong learning so that their skills can remain relevant throughout their working life.The next section will explore what these trends mean for PES and how they can provide relevant, efficlient and effective services in the future world of work.

2.1.4 What does climate change mean for the labour market and PES services?

Climate change will lead to several changes within the labour market as the nature of certain jobs changes and the need for more environmental focused jobs increases. This includes changes such as:

- The emergence of new sectors, such as renewable energy, that require new sets of skills;

- A dicrease or relocation of some traditional industries, such as some types of industrial manufacturing or mining (as examples), due to emerging political priorities around climate change;

- An increase in the need for new techniques and approaches in some sectors, as employees may needto upskill or reskill as certain sectors become more environmentally aware and change their practices accordingly.

Climate change will have implications for the labour market as there is likely to be large cohorts of workers within certain sectors who need to upskill or reskill within their current employment, or in order

to develop skills that are relevant to the labour market and help them make successful transitions to future employment. In geographical areas that are heavily dominated by sectors that are not environmentally friendly, (e.g. such as mining, or forestry) PES may be able to anticipate changes to the local economic profile and develop support packages for enterprises and workers for them to adapt practices and skills to in line with any government policies. In addition, the rise of green jobs is something that PES need to be aware of as it may have implications for the information provided to jobseekers, training opportunities as well as the types of partners they may wish to work with. Green jobs help to:- Improve energy and raw materials efficiency

- Limit greenhouse gas emissions

- Minimize waste and pollution

- Protect and restore ecosystems

- Support adaptation to the effects of climate change10

2.2 What does the future world of work mean for PES?

Globalisation, automation, advances in digitalisation and technology as well as demographic changes will have significant implications for PES in the future. It poses questions such as:

- How can PES use these emerging trends as opportunities to evolve and future proof themselves?

- How can PES work within the future world of work to provide the most efficient and effective job matching services, and how can PES services be adapted accordingly?

- What are the implications for PES’ role in the labour market and how they can strengthen their role within the new world of work?

- What changes do PES need internally in terms of management, training and organisation of work and who and how should PES work with external stakeholders?

This section will outline some of the implications for PES within the future world of work and indicate some of the shifts that may be required to create PES that are agile, robust and fl exible to the needs of the future labour market.

Box 3. International Labour Organisation Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work11

The 2019 Centenary Declaration calls for sustainable development in the future of work and an environment where workers can acquire skills, competencies and qualifications throughout their working lives so that they are equipped for the needs of the labour market.

It identifies that working in multilateral partnerships will become more important in the future of work given the challenges all labour market actors are facing. By working in partnership, actors

will be better positioned to shape the future labour market. This should involve working with representatives from education and training as it is important that the provision of education and training responds to the changing needs of work, and that workers are informed of opportunities for decent work. In addition, it recognises that:- There is a need to develop effective policies to create full, productive and freely chosen employment and decent work for all, particularly facilitating the transition from education to work and young people are effectively integrated into work.

- Measures are in place to help older workers to maximise opportunities that allow them to have good quality, productive and healthy conditions until their retirement.

- Promotion of workers’ rights is important for inclusive and sustainable growth, recognising that workers’ have the right to collective bargaining.

- Support is required for the large and small and medium-sized enterprises in the private sector so that they are able to create jobs, contribute to economic growth, and help to improve living standards for all.

- Effective measures should be in place to support people through the transitions they will face throughout their working lives.

The Declaration also calls for gender equality and social dialogue and tripartite cooperation to assist with policy decision-making.

Figure 2.3 Elements of PES coordination in the labour market

2.2.1 What will the role of PES be? A coordinating role

Firstly, the future world of work provides PES with an opportunity to move into a central, coordinating role in the labour market. PES often have insights into the employment landscape in their localities, the obstacles and barriers faced by jobseekers and insights into enterprises’ needs. In addition, PES may have responsibility for, or at least provide information towards, social assistance programs and/or social insurance benefits. This is particularly important as social protection is considered to be a human right and essential to enable workers and their families to navigate future transitions.12

The ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202)13 calls for better integration between employment and social policies. It states that when designing and implementing national social protection fl oors countries should:

- Combine preventative, promotional and active measures, benefits and social services;

- Promote productive economic activity and formal employment through considering policies that include government credit provisions, labour inspection, labour market policies, tax incentives and that promote education, vocational training, productive skills and employability;

- Ensure coordination with other policies that enhance formal employment, income generation, education, literacy, vocational training, skills and employability, that reduce precariousness and promote secure work, entrepreneurship and sustainable enterprises within a decent work framework.

This means that it is important for the work of PES to be planned and carried out in conjunction with other partners to ensure that there are synergies and complementarities between employment and social programme design and implementation. This implies that PES play, and will continue to play, an important role in the labour market as they can coordinate with other actors to deliver integrated employment and social policies. The European Network Public Employment Services calls this the role the ‘conductor’ of the labour market.

To deliver integrated employment and social policies, PES can do the following:

- Establish dialogue with other ministries, or government departments (e.g., those responsible for social protection);

- Reach out to external providers and stakeholders to engage in dialogue and sharing insights and views around developing and delivering employment and social policies (e.g., this could be via bilateral meetings or round table discussions);

- Delivering communication activities to enterprises and other target audiences in conjunction with other actors, such as other ministries, to show a joined-up approach.

As a result of such actions, the reputation of PES can be enhanced over time as they continually put themselves at the forefront of labour market developments and showcase their knowledge and insights.

2.2.2 How can strategic and delivery partnerships for employment be built?

Secondly, establishing working partnerships for employment with external stakeholders will become more important in the future labour market. Working with organisations such as other ministries, training providers, employers and workers’ organisations will help PES to design effective services that are fit for purpose, support different types of transitions in the labour market and meet new, emerging needs from enterprises. Ultimately, developing partnership for employment and engaging in social dialogue will put PES at the forefront of labour market developments, inclusive pro-employment actions and efforts to reduce the gap between education and work.

Building on existing partnerships and creating new partnerships can offer benefits to all aspects of PES organisation and service delivery, as well as policy and strategy planning and design. External stakeholders can provide valuable insights and views that can be used to shape strategy decisions. This will be important going forward in the future of work as the ILO calls for the importance of collaborative working to delivery social contracts that protect vulnerable workers in terms of their position in the labour market as well as their rights.16

PES need to work with partners to develop collective understandings, as well as concrete actions, around what vulnerable workers can contribute to the labour market and how this can take place.

In addition, PES will increasingly need to build multi-sector partnerships that help to create smooth transitions for jobseekers. School-to-work transitions will likely be accompanied by more work-to-work transitions in the future labour market. PES will need to vary which external partners they work with according to the needs of the target group so that delivery can be agile and appropriate and so that wider issues can be accounted for in strategy design. In particular, a shift from stand-alone services to joined-up provision and partnership working will become much more important for disadvantaged groups.17 This will need a shift towards proactively seeking out new partnerships as and when required to address any new emerging issues. By being proactive and having holistic partnerships, PES will be better positioned to responsive support to jobseekers and thus contribute to a better functioning labour market.

Box 4. Partnerships: Lessons learnt from the European Youth Guarantee18

Collaboration with partners is important as no one single organisation can provide successful solutions to certain target groups, such as young people not in work, education or training. Experiences on the ground in Belgium and Germany, as part of the European Commission’s Youth Guarantee, show that working with partners such as NGOs, trade unions and youth welfare services it is possible for PES to work with others to deliver holistic services to young people who are furthest from the labour market.

Important lessons for working in partnership include:

- Have robust agreements in place from the beginning with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, based on shared and understood commitment.

- Agreements should also include shared and understood targets, mutual support mechanisms and regular monitoring arrangements.

Partnership working should also aim to create:

- Accessible support services, in a relaxing informal and welcoming atmosphere (for young people in particular).

- The opportunity for young people to have a designated case worker, who can guide them through interactions with different providers and help the young person to make an informed choice.

- A common approach and agreed criteria across the partnership.

2.2.3 How can core services be updated and why?

The advances in digitalisation and the potential offered via online delivery will lead to changes in how core services are delivered and what information is provided via core services. This is so that services can remain relevant to jobseekers’ and enterprises needs and is easily accessible to all. In addition, it will also help to guarantee that information offered by PES (either by counsellors, ALMPs or other sources) is pertinent to the needs of the current and future labour market and can contribute to creating well informed and well equipped jobseekers who have the appropriate skills for their future career paths.

The biggest change in the design and delivery of core employment support services in the future labour market is likely to be the move towards online services as a first port of call for jobseekers and enterprises, moving away from intense face-to-face counselling and support. By providing online services, jobseekers and enterprises can access information, search for jobs and upload vacancies from any location, at any time. It is hotly debated across Europe as to whether online services are more cost effective than face-toface and additional services. For example, the Netherlands are undertaking a randomised control trial to see if face-to-face and additional services contribute to a faster return to work compared to standard online services within one year.19

However, digital services are here to stay and will play an important role in the future labour market. As skilled, IT-literate jobseekers can access information online and undertake their own job search, PES may see that face-to-face frontline counselling is primarily accessed by jobseekers who are the furthest from the labour market, for example long-term unemployed, those who do not have a level of IT literacy or other vulnerable groups. This means that while frontline counsellors’ individual caseloads may slightly reduce in the long term as the types of jobseekers that they are engaging with are likely to require more intensive support. This has implications for the allocation of resources to frontline counsellors and the resources and investment required for fully fl edged digital services.

Increasing the accessibility of PES services in the future labour market is also likely to affect the opening hours of PES offices. The traditional Monday to Friday 9am to 5pm opening hours do not suit jobseekers who have other commitments such as childcare or family arrangements, part-time (or full-time employment), studies or other commitments. Therefore, PES may need to adjust these opening hours going forward so that they increase accessibility to different types of jobseekers. For example, this could include ‘late’ opening hours at least once a week and being open on Saturdays. Such decisions may need to be made on a local scale according to jobseeker typologies and available resources.

Information provided via core services also needs to be reviewed and updated in line with the emerging trends in the future of work. This is so that information available via counselling, online information as well as active labour market programs (ALMPs) is up-to-date, relevant and suitable to equip and empower jobseekers with appropriate skills, knowledge and competences for today and tomorrow’s labour market. For example, ALMPs may need to shift their focus according to the needs of enterprises and emerging required skill sets so that jobseekers have skills that fit the needs of the workplace. To do this, PES can work closely with enterprises’ representatives and sector specific bodies to regularly review the contents of any work-preparation ALMPs, or vocational training, is suitable.

In addition, it will be important for frontline PES counsellors to be trained and able to provide information on opportunities available via forms of atypical employment, such as opportunities available in selfemployment and the gig economy. PES counsellors will require training on such employment routes so that they can adequately inform jobseekers. Consequently, PES counsellors will need to develop knowledge of workers’ rights, contract types and working conditions in the gig economy. This is so that they can provide jobseekers with a holistic and informed viewpoint.

2.2.4 What can PES offer around career guidance and lifelong learning support?

Career guidance and facilitating lifelong learning are likely to become much more important activities for PES in the future labour market as there becomes an increasing need to invest in skills.

With demographic changes and ageing populations more workers are likely to require some form of assistance to help them to adapt to the needs of the labour market. This includes via reskilling and upskilling to assist them with changing their career pathways throughout their working life. PES currently provide some form of career guidance via counselling services, however their role around this will be redefi ned and enhanced around this aspect in the future labour market.

PES will be required to provide career guidance and information on labour market possibilities to young people before they enter the labour market. This is so that they can develop the skills, knowledge and competences that are relevant to the labour market, information around realistic expectations, and they have information on job search techniques, tools and PES services. PES may want to target such support services to young people at risk of not entering employment, education or training so that they are not ‘lost’ within the system. Such early interventions can provide young people with the skills and knowledge that they need to make successful school to work transitions and empower them to make successful work to work transitions so that they can take control of their own future career pathways.

In contrast, PES will increasingly see more older workers who are wanting to work for longer and need to revisit their skill sets so that their skills can remain relevant to the labour market. Some of these older workers may need support with job searching (in some cases) or they may need additional training to support their next career move. This may help older workers to move from unemployment to work or from work to work transitions. This means that PES will increasingly need to take a role within lifelong learning by signposting users to relevant learning opportunities and services that relate to reskilling and upskilling.

The increasing stress on lifelong learning will lead to a greater importance of vocational education and training programmes within ALMPs. Such programmes can provide workers with practical on-the-job experiences as well as sector-specific skills and training that can put workers in a better position when applying for jobs. This is particularly important in cases where there are new or emerging sectors within a local, or regional, area and workers need to develop appropriate skills.

In order to provide career guidance and lifelong learning support PES must work together with different types of partners in order to provide support to different types of transitions. Support needs to be appropriate to the target group and likely support requirements. For example, for young people PES can work closely with the education ministry, social services, schools and education providers to deliver targeted support to young people including more specific support to those who are deemed at risk of dropping out of education. Further information on services to disadvantaged young people is provided in Section 5.

In the longer term, PES may want to work very closely with partners to develop a ‘one-stop-shop’ for career guidance and lifelong learning information and advice. This is where jobseekers can visit one specific office and receive information from different partners on different aspects such as unemployment benefits, health, housing, childcare and other aspects. The Ohjaamo example (see Case Study 1) demonstrates how the PES in Finland have worked with multi-sector actors to develop a network of offices that provide guidance to young people at risk. This is an approach that has proved beneficial in targeted young people under 30 years old, reduces any preconceived views about PES and PES services and the model could be transferred to other situations.

As part of the ‘Work for a brighter future – Global commission on the future of work’ report by the ILO, they call on governments to invest in people’s capabilities and for learning to become a given entitlement. For this to take place, skills policies, employment services and training systems need to be adjusted to allow workers’ time and financial support required to learn. Such an ‘employment insurance’ system or ‘social funds’ could be established as a way to fund workers’ training and continuing education. This would be beneficial to all workers including those who are self-employed or employed by smaller companies who may not otherwise have such opportunities.23 A move towards offering career guidance and support around lifelong learning opportunities would expand and re-define PES service offers. This would require working with a much wider range of stakeholders, establishing formalised partnerships (where they do not already exist) and really strengthening the role PES play within the wider labour market.

Box 5. Key policy principles on lifelong learning

The ILO24 has identified a number of key policy principles on lifelong learning. These include: u “Members should formulate, apply and review national human resources development, education, training and lifelong learning policies which are consistent with economic, fiscal and social policies” (ILO 2004, p. 2);

- That the social partners have a particularly important responsibility in “supporting and facilitating lifelong learning including through collective bargaining agreements” (ILO 2008, p. 14);

- That “as part of the lifelong learning agenda”, governments should provide “employment placement services, guidance and appropriate active labour market measures such as training programmes targeting older workers and, where possible, supported by legislation to counter age discrimination and facilitate workforce participation“ (ILO 2008, p. 9);

- “That members should develop a national qualifications framework to facilitate lifelong learning” (ILO 2004, p. 3);

- “That members should promote equal opportunities for women and men in education, training and lifelong learning” (ILO 2004, p. 3);

- “That members should recognise employees’ rights to free time for training through paid study leave” (ILO 1974, p. 1); and

- That a holistic approach includes “development of core skills – including literacy, numeracy, communication skills, teamwork problem solving and other relevant skills and learning ability, as well as awareness of workers’ rights and an understanding of entrepreneurship, as the building blocks for lifelong learning and capability to adapt to change” (ILO 2008, p. 2). Source: ILO (1974), ILO (2004), ILO (2008)

2.2.5 What are labour market information systems and how can these be used in relation to services for jobseekers?

Labour market information systems can provide robust and accurate statistics, which can make it possible for countries to report on labour market indicators relating to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)25. In order to report on all the SDG labour market indicators in a timely manner and using comparable, accurate statistics, countries must have in place a robust labour market information system that consolidates all available statistical sources.

Labour market information systems are an important foundation for developing well-informed evidencebased decision making, which can inform the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies. This can in turn help to make services for jobseekers much more efficient. They have three main functions:

- Facilitate labour market analysis;

- Provide a basis for monitoring and reporting on employment and labour policies;

- A mechanism to exchange information, or work with different actors and organisation that may produce labour market analysis (e.g., universities, research bodies).

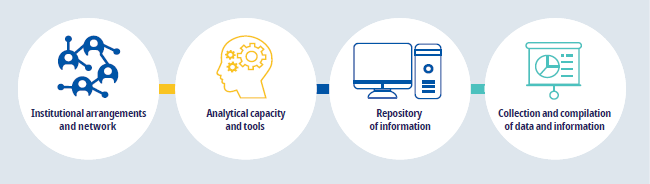

The figure below demonstrates the four main components of labour market information systems.

Figure 2.4 Components of labour market information systems26

Having labour market information systems in place can help PES to identify future trends in the labour market and skills gaps. The insights gained can therefore be used by PES to shape career guidance and wider services for jobseekers to deliver services that make a real difference to jobseekers and help to empower them to move forward in the future labour market.

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Work for a brighter future – Global Commission on the Future of Work’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ Adapted from ILO (2019) ‘Technical Note 2: Instruments concerning public employment services: Fifth meeting of the SRM

TWG: Examination of instruments concerning employment policy and promotion’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_norm/-normes/documents/genericdocument/wcms_715384.pdf) and European Commission (2018) ‘The Future of Work:

Implications and responses by the PES Network’ (https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=20520&langId=en) - ^ ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work (2019) (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_norm/-relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_711674.pdf)

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ ILO (2016) ‘Non-Standard Employment Around the World: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects. Overview’ (page 2) (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-dcomm/-publ/documents/publication/wcms_534496.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2016) ‘The rise of the «just-in-time workforce»: on-demand work, crowd-work and labour protection in the «gigeconomy» (page 21) (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_protect/-protrav/-travail/documents/publication/wcms_443267.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2018) ‘Digital labour platforms and the future of work Towards decent work in the online world’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-dcomm/-publ/documents/publication/wcms_645337.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2016) ‘Non-Standard Employment Around the World: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects. Overview’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-dcomm/-publ/documents/publication/wcms_534326.pdf)

- ^ https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/news/WCMS_220248/langen/index.htm

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work (2019) (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_norm/-relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_711674.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Global commission on the future of work – Work for a Brighter Future’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:3065524:NO

- ^ https://www.ilo.org/secsoc/areas-of-work/legal-advice/WCMS_205341/langen/index.htm

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Work for a brighter future – Global Commission on the Future of Work’ (available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Global commission on the future of work – Work for a brighter future’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2018) ‘ILO briefs on Employment Services and ALMPs’. Issue No. 1 ‘Public employment services: Joined-up services for people facing labour market disadvantage’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_632629.pdf)

- ^ European Commission (2018) ‘Activation Measures for Young People in Vulnerable Situations. Experiences from the ground‘ (https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=20212&langId=en)

- ^ European Network of Public Employment Services (2017) ‘PES Network Seminar on Piloting and Evaluation’ (available here: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19254&langId=en)

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Work for a brighter future – Global Commission on the Future of Work’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Lifelong Learning: Concepts, Issues and Actions’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_emp/ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_711842.pdf)

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19409&langId=en and https://ohjaamot.fi/haku

- ^ ILO (2019) ’Work for a brighter future – Global commission on the Future of Work’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Lifelong Learning: Concepts, Issues and Actions’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-ed_emp/-ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_711842.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2018) ‘Decent Work and the Sustainable Development Goals A Guidebook on SDG Labour Market Indicators’ (https://www.ilo.org/ilostat-files/Documents/Guidebook-SDG-En.pdf)

- ^ https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/dw4sd/themes/lm-info-systems/langen/index.htm

- 2.1 What are the emerging trends in the future of work and what are the implications for PES?