- Contents

- Introduction

- Labour Force Surveys

- Table 5.1. Some lessons learned from the BLS study

- Table 5.2. Questions relative to digital platforms work

- Information and Communications Technology (ICT) use survey

l

Introduction

Digital platforms are a multi-domain phenomenon, which can be observed either from the point of view of the worker, the client or the platform itself. High-quality statistics on digital platforms can inform about their impact on the labour market evolution and on its economic and social aspects. This has an implication on the sectoral structure of the economy but also on the technological evolution, on the production innovation process and recently also on the cultural evolution, with new terms entered in the vocabularies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these platforms entered into own lives, helping in delivery of goods for confined populations and in working from home for those who were living under restrictions.

This variety of dimensions is discussed in Chapter 4, which describes different information sources according to different information needs and different domain of analysis. Information needs are driven by different policy interests and concerns: tax authorities, employment ministries, national accounts analysts and others will propose different operational definitions of the phenomenon and will use different sources accordingly.

Chapter 5 aims to be more practical, looking at actual measurement experiences. This chapter builds on evidence drawn from different testing exercises to generate standard questionnaires and methodologies for various types of surveys or other sources.

Its objective is to describe the initiatives from different institutions that undertook some actual measurement on the digital platform employment (DPE), in order to learn from these experiences and provide recommendations for the future. Most of the experiences discussed in the chapter are still experimental and do not rely on established methodologies, this is a contribution to build a shared measurement framework based on common vocabulary, common definitions and even a common understanding of the phenomenon.

Different members of the Technical Expert Group contributors have contributed to this chapter, bringing their experiences on generating information on DPE from different sources. In order to harmonise their contributions, and to facilitate comparisons, a common template was provided to authors, asking them to describe:

- Original purpose of the initiative: Investigating which are the objectives and underlying questions the measurement experience aims at answer. For example, if the interest is in the quantitative dimension of the phenomenon, how many persons involved in DPE are in the population? If the interest is on the qualitative labour market features then the questions can be which are the DPE persons’ characteristics or which are their background features (demographic, education, previous experiences)? If the interest is on the social aspects of the market then the questions can be which are their working conditions? Or which is the degree of formality/informality of the working arrangements? If the interest is on the work itself then the question is which are the features of the job (driving, delivery, services to household, freelance such as program coding/translation)? If the interest is on the technical and innovation features then the question can be which is the type of the platforms (providing online or on-location work) and how many are they?

- Reference population and sampling: Providing a description of the statistical units (that can be households, individuals, enterprises, platforms). According to the population, different sampling techniques can be applied and should be here clarified. The coverture is also interesting: does the survey reach the entire population with uniform inclusion probability or has the sample been extracted in order to focus one particular sub-population? The dimension of the sample of course also determine the statistical significance of the measure.

- Other relevant survey features: Any other relevant feature such as time references, data collection mode (Personal, telephonic, web based, …) and any other methodological choices. This is particular important to compare different sources: yearly data is necessarily different from data referring to a single week.

- Implied operational definition: General and operational (often only implicit) definitions of the analysed concepts. With, if possible, a description of the consequences of the practical definition chosen. For example it may be that some parts of the phenomenon are excluded, that some platforms are not considered, or other limitations due to the boundary built around the definitions. This should be linked to the conceptual framework as described in Chapter 3. The main questions are:

- does the operational definition include goods and/or services (for example only include the provision of services but not production of goods)?

- is it limited to some specific types of digital platforms (for example restricted to digital labour platforms only, with the exclusion of other specific types of platforms such as Airbnb, YouTube, Instagram, or includes only platforms with direct intermediation i.e. triangular relationship)?

- is it restricted to a specific employment status, for example own-account workers only excluding employees or volunteer work?

- is it limited by any other implicit or explicit restriction (only telephonic apps, only web browser platforms, only national based platforms, …) and definition used (is there a definition for algorithm, for platform, for employment (ILO strict concept or larger))?

- Obtained goals and lessons learned: Possibly including some figures, some policy consequences already actuated (if relevant), a list of do and do not for the future and a short presentation of lessons learned about a better understanding of the DPE market or at least on how to measure it. This is also the template used to present the measurement experiences reviewed below. The last section distils some statistical recommendations from these experiences that, in the TEG’s view, should guide future statistical endeavours in this area.

Labour Force Surveys

Labour Force Surveys (LFSs) collect information on the supply side of the labour market, i.e. from worker’s perspective. Sampling units are either households or individuals, but the aim is always to provide information on individuals belonging to the (non-institutional) resident population. Given the large reference population, LFSs are well suited to capturing general dynamics of participation rather than to provide detailed information on small phenomena: even if their sample is large, the probability to include in the sample enough observations on small phenomena is low. While LFSs are a potentially good solution to estimate the total number of digital platform employed persons, they lack in statistical precision when studying particular characteristics of sub-groups of workers in DPE. Generally, LFSs are fit for quantitative analysis but if a qualitative analysis is needed then a smaller survey, with a more focused reference population, can provide more details. Several countries experimented (or are experimenting) the use of the LFS in the DPE domain.

US Bureau of Labour Statistics

Original purpose

The Current Population Survey (CPS) is the US monthly Labour Force Survey from which the official unemployment rate, alongside with other measures about the work force, are derived. In May 2017, BLS added four questions about digital platform employment (DPE) to the periodic CPS supplement on workers in “contingent and alternative work arrangements” (CWS).

The purpose of these four DPE questions was to measure the number of people employed as digital platform workers in the United States. By virtue of the DPE questions being asked as part of a supplement to monthly CPS, the questions also were designed to obtain demographic information and job characteristics of digital platform workers. For example, dependent on the estimated number and sample size, the gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, immigration status and educational attainment of digital platform workers could be quantified and compared to those of non-digital platform workers. The industry, occupation, usual and actual hours worked, multiple job holding status and earnings of digital platform workers could also be examined. Using information collected in other parts of the CWS module, information about whether digital platform workers have health insurance, the source of health insurance for those who have it, and job search activities could also be explored.

The original intention of these supplementary questions was to determine whether digital platform workers engaged in this type of work as their primary job or as secondary work. The DPE questions also were designed to distinguish between location-based platform workers (where tasks are performed offline in real physical locations) and online web-based platform workers (where tasks are performed online and remotely by workers). No other information about platform work (such as the names of the platforms used, the platform’s work rules, or how workers obtain assignments from the platform) was collected through these questions.

Reference population and sampling

The reference population of the monthly CPS is the US non-institutional population age 16 and older. Because the DPE questions were part of a supplement to the CPS, the sample design was the same as that of the CPS. The CPS uses a multi-stage, stratified random sample of approximately 72 000 housing units from 852 sample areas throughout the United States. Use of this reference population also allows estimates to be in accord with other US labour force measures.

Other relevant survey features

The CPS is typically conducted in the week containing the 19th of the month, and asks respondents about their activities in the prior week. To DPE questions were asked to individuals who had been classified as employed during the week of May 7- 13, 2017. As with the monthly CPS, the DPE questions were asked by Census Bureau interviewers using a computerized questionnaire. These interviews were conducted using a combination of in-person and phone interviews. Phone interviews were conducted either from interviewers’ residences or from centralized facilities.

Implied operational definition

The questions included in the CWS module of the CPS were:

Introduction - I now have a few questions related to how the Internet and mobile apps have led to new types of work arrangements. I will ask first about tasks that are done in-person and then about tasks that are done entirely online.

Q1 Some people find short, IN-PERSON tasks or jobs through companies that connect them directly with customers using a website or mobile app. These companies also coordinate payment for the service through the app or website.

For example, using your own car to drive people from one place to another, delivering something, or doing someone’s household tasks or errands.

Does this describe ANY work (you/NAME) did LAST WEEK?

Q1a Was that for (your/NAME’s) (job/(main job, (your/NAME’s) second job)) or

(other) additional work for pay?1

Q2 Some people select short, ONLINE tasks or projects through companies that maintain lists that are accessed through an app or a website. These tasks are done entirely online, and the companies coordinate payment for the work.

For example, data entry, translating text, web or software development, or graphic design.

Does this describe ANY work (you/NAME) did LAST WEEK?

Q2a Was that for (your/NAME’s) (job/(main job, (your/NAME’s) second job)) or (other) additional work for pay?

The questions about DPE workers in the CPS supplement operationally defined DPE workers as workers who obtained tasks, job or projects through an online platform, and whose customers used the same online platform to pay for the services provided. This operational definition of DPE workers encompasses both location-based platform workers (e.g. rideshare drivers, delivery workers, and home service providers) and online web-based platform workers (e.g. web developers, translators, and content mediators). To be counted as a DPE worker in the CPS supplement, individuals must be employed. People involved in volunteer work, unpaid trainee work, and own use production work are therefore excluded, even if their work was done through or on a digital platform. All types of employed individuals can be DPE workers, except unpaid family workers. Self-employed (own account workers) can be classified as DPE workers regardless of whether they have employees or are incorporated businesses.

The CPS definition of DPE workers, by virtue of the questions wording and their restriction to those who are employed, only includes workers using digital labour platforms. By asking about tasks or jobs that people obtain through an app or website, this definition implicitly excludes individuals with income generated from the selling of new or used goods online. This definition also implicitly excludes those who generate income from the rental of property and activities associated with generating this income. However, direct questions to screen out these activities were not explicitly asked - it should be noted that these exclusions from the definition of DPE workers did not preclude from being counted as employed individuals doing activities associated with the production of goods to sell and the rental of property.

The requirement that customers pay through the same platform used to connect workers with customers further restricted the CPS measure of DPE workers to workers where digital platforms provide at least some direct intermediation (triangular relationships). The CPS definition does not make any other restriction based on the type of intermediation platforms implement, while permitting platforms to have varying degrees of control over how workers are assigned work (algorithmically or not), the price customers are charged, and other forms of direct intermediation. This same requirement (that customers pay through the same platform) implies that workers conducting a job search online for non-DPE jobs (e.g. posting resumes online, reviewing online job postings or conducting online job interviews) and workers advertising for customers online on their own (e.g., using an electronic bulletin board such as Craigslist) are excluded from the CPS definition of DPE workers.

Workers conducting a job search online for non-DPE jobs (e.g., posting resumes online, reviewing online job postings or conducting online job interviews) and workers advertising for customers online on their own (e.g., using an electronic bulletin board such as Craigslist) are excluded from the CPS definition of DPE workers by the requirement that customers pay through the same platform used to connect to workers.

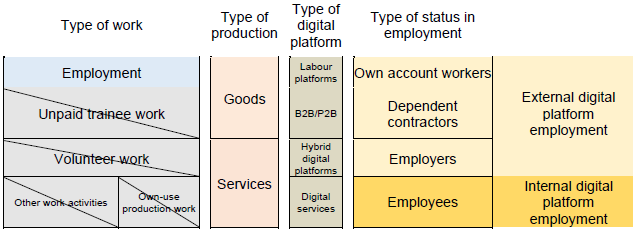

Figure 5.1. Implied conceptual scope for the BLS study

Based on the data collected through these questions, BLS released estimates about the number and characteristics of digital platform workers. Doing so, however, required modification of some of BLS’s standard procedures. In particular, after extensive review of the collected data, BLS determined that the new questions did not work as intended and included a large number of incorrect “yes” answers. To eliminate these “false positives”, BLS manually recoded answers using additional information collected in the CPS survey. This recoding reduced the number of “yes” answers by approximately two-thirds. BLS is confident that the recoded data provides a better picture of location-based and online web-based platforms workers. In the interest of transparency both the data as originally collected and recoded were released to the public.

BLS analysis of its recoded data indicates:

- In May 2017, there were 1.6 million digital platform workers in the United States, accounting for approximately 1% of total employment.

- Digital platform employment was fairly evenly divided between location-based and online webbased platforms. Location-based platform workers accounted for 0.6% of total employment, while online web-based platform workers accounted for 0.5% of total employment.

- Digital platform workers were slightly more likely to be men than women, reflecting the fact that, overall, a higher percentage of the employed in the United States were men.

- 17% of digital platform workers were Black, higher than their share of overall US employment (12%). By contrast, 75% of platform workers were White, slightly lower than their share of workers overall (79%). Hispanics made up 16% of platform workers, and Asians accounted for 6% of platform workers, close to their shares of total US employment.

- Black people were overrepresented among location-based platform workers (23%), while White people were overrepresented among online web-based platforms workers (84%).

- Digital platform workers were more likely than workers overall to work part-time. (Part-time workers are defined as those who usually work less than 35 hours per week at all jobs combined.)

Additional information about the characteristics of digital platform workers can be found on the BLS website https://www.bls.gov/cps/electronically-mediated-employment.htm. This website refers to digital platform employment as “electronically-mediated-employment”; it also refers to “location-based” as “in person” and to “online web-based” as “online”.

Lessons learned

Based on a long-standing tradition, BLS does not use the names of companies in its survey questions, particularly in emerging or rapidly changing industries. BLS avoids the use of company names both to avoid focusing respondents on just a few, particular companies and to ensure that the questions are durable across time (or even between when the questions are developed and when they are fielded). To distinguish between people in various categories, BLS relies on asking questions about characteristics that distinguish the group of interest. This is the approach that was used with the DPE questions. However, due to other constraints, only 4 questions could be used to identify DPE workers.

Both the nature of platform work and the constraints of only having 4 questions contributed to the questions not working as intended. Specifically, the questions used in the CWS to identify location-based and online web-based platform workers were too complicated. Due to the length of the question, it appeared that at least some respondents did not hear the part of the question related to customers paying through the platform. The complexity of the questions also caused some respondents to focus on the examples, rather than on the characteristics of platform work embedded in the question. Additionally, if respondents hesitated, interviewers sometimes repeated only the examples.

Another issue with the questions, is that respondents interpreted them too broadly. This broad interpretation was related both to the widespread use of apps, computers, and websites by people in all types of work and to the complexity of the questions. This broad interpretation occurred for workers who were connected to customers through a website or app as part of their work but were not paid through it (such as customer service workers or fast-food preparers), workers who used mapping apps to obtain routing directions to customers (such as gravel deliverers) and workers who used computers as part of their work (such as receptionist who schedule medical appointments using a computer and university lecturers teaching online). Respondents with these broad interpretations appeared to have not heard the part of the question asking if customers paid through the same app or website that connected workers to them.2

Despite the difficulties with the questions, BLS will continue to use questions asking whether people have certain work characteristics associated with being platform workers to identify platform workers in the future. BLS will also not use the names of companies as it ensures the largest coverage at a point in time, is most likely to maintain durability of the measurement across time and provides the most flexibility for data users. Several do’s and don’ts have been learned about following this approach, however.

Table 5.1. Some lessons learned from the BLS study

Do Do not • Collect information on several characteristics that define platform workers and distinguish them from workers who just use the digital technology as part of their work • Just rely on whether workers connect to customers via an app or website to identify workers as platform workers • Ask about characteristics being used to establish a person as a platform worker in separate questions • Combine several characteristics and examples into a single question • If interested, ask about whether platform workers are location-based or online web-based as a single follow-up question after establishing workers are platform workers. • Write a set of questions to identify location-based platform workers and a separate set of questions to identify

online web-based platform workers.

• Collect sufficient information in the survey to verify whether digital platform workers are correctly identified (this can include the name of the platform workers used) • Test the questions on both those who are platform workers and those who are not. For the group who are not platform workers, include both those who perform similar tasks to platform workers and those who do not (e.g., workers who use computers or the internet as part of their work, but have

work arrangements that are very different than platform workers)

• Only test the questions on platform workers or workers who perform tasks similar to platform workers • Only test the questions using online panels either non-probability (e.g., mTurk, and Qualtrics) or probability

(e.g., Knowledgepanel)

• Monitor survey collection to determine if questions worked as intended Source: Eurostat and OECD based on US Bureau of Labour Statistics

Switzerland – Federal Statistical Office

Original purpose

In 2019, Switzerland conducted an LFS ad-hoc module on “internet-mediated platform work”. The main objective was to estimate the number of internet-mediated platform workers in the country, with additional questions on the reasons for this type of work, on how long the person has been providing these services, whether they take place as a main, second or additional job, the regularity and number of hours worked, the income generated, and the name of the platform or app. All types of services were considered (renting out accommodation, taxi services, sale of goods, and other services). The names of platforms or apps were mentioned as examples in the filter questions.

Reference population and sampling

The reference population of the module covered 15 to 89 year-olds from the permanent resident population. No specific sub-population was targeted and the questions were asked to all persons independently of their labour market status. The total annual sample of the module was around 12 000 persons which were chosen by random selection at the end of the first wave of the LFS (one-third of first wave, two-thirds being already moduled).

Other relevant survey features

In general, the questions on the internet-mediated platform services referred to the last 12 months preceding the interview. In order to have information on work done in the reference week, an additional question was used to find out if the person had provided one of the named services in the past week. All interviews were conducted in CATI.

Implied operational definition

In the Swiss module, every type of internet-mediated platform service was considered, including renting out accommodation via Airbnb or selling goods. Four filter questions allowed distinguishing between platform work in the narrower sense and platform services as a broader concept, including those selling goods and renting out accommodation. The following criteria had to be fulfilled for platform work or platform services:

Internet-mediated platform work:

- The person providing the service is connected to the client via an internet platform or app.

- Payment is usually made via the internet platform or app.

- The vast majority of the services provided consist of work (e.g. cleaning) and not of assets (e.g. renting out accommodation).

All areas of activity that can be processed via an internet platform or app are included, such as taxi services, cleaning, food delivery services, transport and delivery of goods, tradesperson services, programming, translation, data and text entry, and web and graphic design.

Other internet-mediated platform services:

Online rental of accommodation (rooms, apartments, and houses)

- The person providing the service is connected to the client via an internet platform or app.

- Payment is usually made via the internet platform or app.

Online sales via an internet platform

- The person providing the service is connected to the client via an internet platform or app.

- The goods sold must have been deliberately collected, bought or produced for the purpose of resale.

- Payment is not usually made via the internet platform or app.

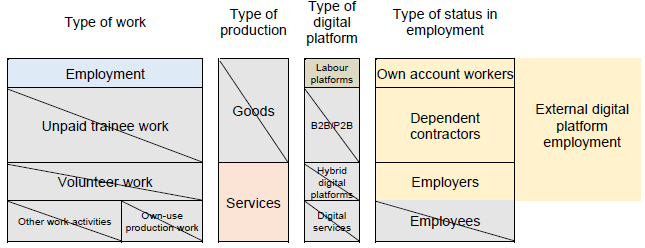

Figure 5.2. Implied conceptual scope for the FSO study

The analysis of the Swiss module showed that in 2019, 0.4% of the population said they had carried out work via internet-mediated platforms in the past 12 months (taxi services: 0.1%; other services such as programming, food delivery, cleaning, etc.: 0.3%). At 0.6%, a slightly larger percentage of the population had rented out accommodation through an internet platform, and 0.8% of the population had sold via an internet platform goods that were especially collected, purchased or produced with the aim of reselling them.

Lessons learned

As this form of work is not very common in Switzerland, it is difficult to collect data on these specific types of activities and to formulate questions in a way that reflects the conceptual issues at stake and that is understood correctly by the respondent. There was confusion between providing and using a service via a platform / app and consequently a certain number of “false positives”. Plausibility checks based on the hours worked, income, named platform, reason for activity, but also the interviewers’ comments were very important in the data production process.

Based on these first experiences, Switzerland reflected on potential improvements of questions. One suggestion would be to add, after a positive answer to the filter questions, a question on payment and commission:

-“Have you been paid / will you be paid for this service?” Answer categories: via the platform, app / by the client / won’t be paid

-“Does the internet platform / app take a commission for the service* you offer on it?” Answer categories: yes / no.

*renting out an accommodation / taxi services / sale of goods / other service

A second suggestion concerns the sale of goods to better capture the persons who acquired goods with the specific aim of reselling them and to generate income. If the respondent says “yes” to the filter question on sales of good, there would be a follow-up question:

“Why did you sell these goods?” Answer categories: I didn’t need them anymore / I collected, bought, or produced them with the specific aim of reselling them

These additional check questions would help to exclude a significant number of false positives, i.e. persons answering “no” to payment and commission; and persons selling goods because they didn’t need them anymore.

Chile – National Statistics Institute

Original purpose

Since January 2020, the National Employment Survey (ENE, Spanish acronym) has incorporated a new series of updates in order to strengthen its production process and more accurately reflect the national labour market. These improvements include expanding the questionnaire to include new dimensions of analysis in order to capture new trends in the Chilean labour market.

Through these processes, the ENE began to capture, measure, and analyse employment work that uses mobile applications or digital platforms. This kind of work is a recent phenomenon that has been growing at an accelerated pace throughout the world, and it grew further during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, National Statistics Institute (INE, Spanish acronym) can provide information for more research into the nature and trends of employment work in Chile, enabling a response to such questions as “How many people are employed in work obtained through the use of digital platforms?”, “What are their demographic characteristics?”, “In which economic sectors are these workers employed?”, “What is the status of the population employed on digital platform work?”, “How do such workers access social welfare benefits?”, and “Which platforms did they use to obtain work?”

Reference population

The ENE of the INE is the principal survey on the labour force in Chile, and it has publishable information since 1986 to date. The ENE is aligned with the recommendations of the International Conference of Labour Statisticians of the International Labour Organization. The universe of the ENE consists of all persons who reside in occupied private dwellings within the national territory and who are covered by the sampling frame of the survey called MMV 2017.3 Within this universe, the target population of the ENE is defined as the working-age population (i.e., all persons aged fifteen and over) who habitually reside in occupied private households in Chile.

The universe of the National Employment Survey (ENE) consists of all persons who reside in occupied private dwellings within the national territory and who are covered by the sampling frame of the survey called MMV 2017.4 Within this universe, the target population of the ENE is defined as the working-age population (i.e., all persons aged fifteen and over) who habitually reside in occupied private households in Chile.

Sample dimension

Because the digital platform work continues to be a phenomenon in constant change and development, information on as many workers as possible should be captured. For this reason, the question on work obtained through digital platforms in the main activity5 is directed to all occupied persons, except for persons classified as “Contributing family workers” in consideration of the nature of such work. Information on work obtained through digital platforms is also studied among workers who state that they engage in a secondary activity, in order to describe such activities.

Other relevant survey features

The ENE sample is spread over three months, constituting moving quarters, and it is then divided into subsamples that are repeated every three months for a maximum period of one and a half years (six rounds of visits). Thus, the ENE captures information for each monthly sub-sample, but it processes, analyses, and publishes information for moving quarters (INE, 2021[1]).

The information is collected on a mobile capture device (i.e., by CAPI6) in an application designed especially for the ENE. In addition, information is gathered through a mixed methodology that includes face-to-face interviews and telephone surveys.

Implied operational definition

The ENE defines digital platform work as follows: “work that uses a mobile application or digital platform to offer goods or services by exclusively or predominantly using media that involve remote contact with customers, either through the internet (digital platform) or by cell phone (mobile application)” (INE, 2022[2]). In short, platform workers are those who use a digital platform or mobile application to mediate a service or exchange goods.

Because expert international organisations have not yet officially defined this recent and rapidly developing phenomenon, which has a strong impact on employment, published statistics are considered experimental within the framework of the labour market statistics published by INE. The questions included in the ENE questionnaire to capture digital platform work are the following:

Table 5.2. Questions relative to digital platforms work

Employed persons Employed persons with secondary activity F2 Does the person obtain their work through the use of a mobile application or web platform?

A mobile application or digital platform is any computer application that allows a person to perform a varied set of tasks associated with the sale of goods or services.

It should be recorded only when it is used predominantly or exclusively for this work.

Do not include generic names such as internet, website, intranet, software, or similar names.

- Yes. Which one?

- No

88 Not sure

99 No response

G4 Does the person obtain the work of their second occupation through the use of a mobile application or web platform?

A mobile application or digital platform is any computer application that allows a person to perform a varied set of tasks associated with the sale of goods or services.

It should be recorded only when it is used predominantly or exclusively for this work.

Do not include generic names such as internet, website, intranet, software, or similar names.

- Yes. Which one?

- No

88 Not sure

99 No response

Source: National Statistics Institute of Chile, ENE (INE, 2022[2]), Separata técnica n°4: Nuevas dimensiones de análisis.

The structure of the questions is as follows: first, the interviewer asks a dichotomous question on whether this type of technological tool is used while permitting partial response. Next, if affirmative, the interviewer asks the name of the digital platform, “Which one?”. However, the fields intended to identify the digital platform do not have any type of validation during the collection process, thus the open nature of the question may result in errors in the information provided by the respondent. Therefore, the response is subject to cleaning, validation, and imputation.

Once available, the information on the mobile application or digital platform is cleaned. This process consists of standardizing the open text record and eliminating texts determined to be “erroneous”. These texts include names of digital platforms that do not meet the accepted definition of digital platform work. After the texts are cleaned, only those persons who replied with “valid” texts are included in the estimation.

To define a text as valid, a dictionary of digital platforms was created after an exhaustive review of the digital platforms in Chile. The dictionary is constantly being updated in order to reflect the evolution of digital platforms.

After, the question of digital platform work in main activity will be imputed according to the description of the question on employment and activity. This procedure consists of reviewing the text to identify the occupational group, the activity of the company, and the name of the company that pays the person's income, searching in the descriptions of these questions when the employed person states that they obtain work through one of the following mobile applications: Uber, Cabify, Didi, Beat, Cornershop, Rappi, Uber Eats, or Pedidos Ya7. The final variable is published in the database called “plataformas_digitales”. The value of the variable is 1 if it represents those who actually have a digital platform work in their primary occupation. The variable “pd_especifique” represents in which digital platform work. After the process, the variables on secondary occupations of digital platform work, are published as “sda_pd” and “sda_pd_especifique”.

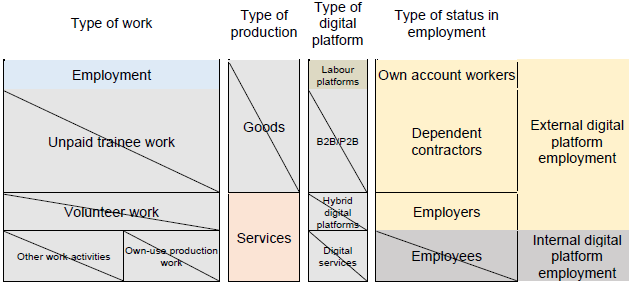

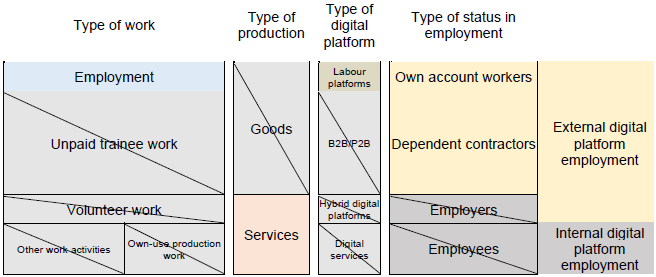

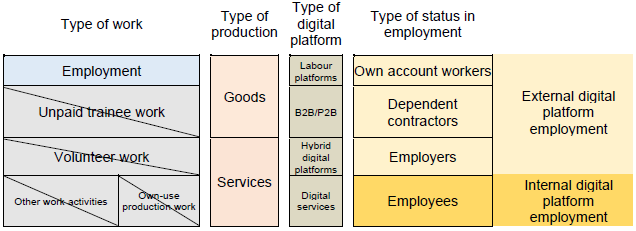

Consequently, we can observe that the conceptual scope of the questions of digital platforms work can be classified by type of production, type of digital platform or by employment status. This can be seen in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3. Implied conceptual scope for the NSI study

Obtained goals and lessons learned

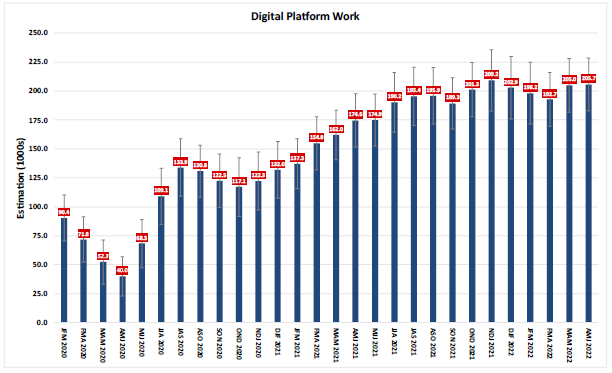

For the moving quarter April-May-June Q2 2022, it is estimated that there were 205 741 employed persons working on their main activity on digital platforms, which represents 2.3% of the total employed population8. Of these 205 741 employed persons, 31 376 were foreign nationals, or 15.3% of the total number of employed persons on digital platform work.

Figure 5.4. Employed people on digital platform Q1 2020-Q2 2022

Source: National Statistics Institute of Chile, ENE (INE, 2022[2]), Separata técnica n°4: Nuevas dimensiones de análisis.

Breaking down statistics by gender, there were 108 630 employed men who work on digital platform, which represents 2.1% of the total number of employed men and 52.8% of the employees on digital platform. In contrast, an estimated 97 111 employed women obtained work on digital platforms, which represents 2.6% of the total number of employed women and 47.2% of the employees on digital platform. For the last moving quarter for which data is available (April–June 2022), 5.3% of the informally work on digital platforms, which amounts to 126,441 persons. In contrast, 1.2% of the formally employed population work on digital platform (45 027 persons). Also, most platform workers are independent (78.1% of digital platform workers that represents 160 713 persons).

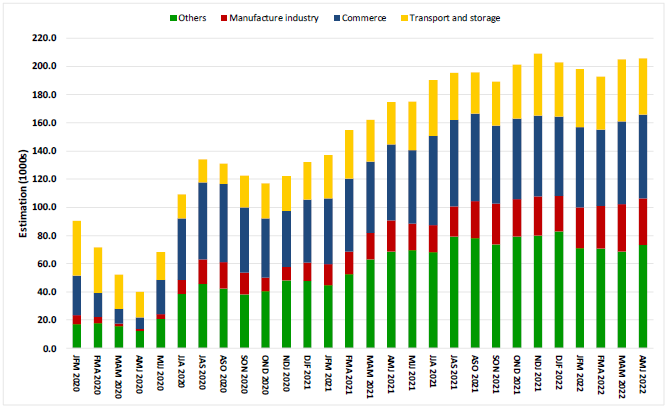

When disaggregated by economic activity, the estimate of employed persons who works on digital platform shows that “wholesale and retail commerce”, represented 28.8% of platform workers. For this group, the following platforms and applications were the most prevalent: Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp. Following is “transport and storage”, which includes vehicle drivers, and it makes up 19.5% of platform workers (40 025 persons) during the period. For this group, the application Uber is the most important. Finally, 33 130 persons were categorised as working in “manufacturing”, which represents 16.1% of platform workers. The activities of this group include the manufacture of textiles and the processing of some food and personal care products.

Figure 5.5. Digital platform work by economic activity Q1 2020-Q2 2022

Source: National Statistics Institute of Chile, ENE (INE, 2022[2]), Separata técnica n°4: Nuevas dimensiones de análisis.

In Chile, Law 21.431, about digital platform work, was enacted in March 2022, and it comes into force on September 2022. This one establishes norms and it regulates the relationship between platform workers (both dependent and independent) and the digital platform company. The Law defines what is to be understood as a digital platform company and digital platform worker. It describes the type of employment contract between dependent and independent digital platform workers, specifying the employer's duty to protect workers, to normalize working hours and remuneration or fees, and respect platform workers' right to access social welfare benefits and their right to disconnection among other contractual obligations.

The law is narrower in its definition of digital platform work than ENE's definition, and therefore information based on the law constitutes a subset of what is captured in the survey. ENE estimate employed persons, and the resulting figures may therefore differ from the number of jobs available on digital platforms because a worker may be registered on more than one platform at the same time. The measurement of the number of digital platform workers has been important in approximating the number of persons who will be affected by the law upon its implementation. The ability to characterise this subgroup of employed persons has provided a framework for the application of Law 21.431, and it has enabled the monitoring of the evolution of the characteristics and working conditions of this subgroup over time.

Finally, the analysis and monitoring of the employed population on digital platform is a new topic in labour force surveys, and information on this subgroup is frequently requested. The ENE has incorporated the observation of this subgroup since 2020 by using a data processing methodology based on text mining, which allows validating and cleaning data according to the definition of a dictionary of digital platforms.

These estimates are defined as experimental statistics because they still show room for improvement, and they have not yet achieved sufficient maturity to be included in the list of official statistics. It should be noted that for the last moving quarter for which data is available (Q2 2022), the total number of employed persons on digital platform reached 205,740 persons, equivalent to 2.3% of the total employed population.

Manpower Research and Statistics Department, Singapore

Original purpose

Singapore’s Labour Force Supplementary Survey on Own Account Workers provides data on the prevalence of own account workers9 engaged in online platform work. Dedicated questions in the supplementary survey allow examining the demographic profile of own account workers engaged in online platform work, the occupations they worked in and, the types of online matching platforms used. Beyond this, the survey also seeks to understand the motivations for taking on platform work, whether the workers involved were doing this as their main job or on the side, and the challenges they faced.

Reference population and sampling

The module considered here is a supplement to the Comprehensive Labour Force Survey, which covers all private households in Singapore. The survey sample is selected based on a stratified random design with proportional allocation.

All respondents aged 15 years and over who indicated in the Comprehensive Labour Force Survey that they did own account work in the past year were questioned through the supplementary survey, which asks for detailed information on their experiences in own account work and whether online matching platforms were utilised. Approximately 4 200 persons responded to this supplementary survey, with results grossed up to the resident population using multiple estimation factors. The use of a random sampling methodology and a high response rate of at least 85% help ensure that findings are representative of the general population.

Other relevant survey features

The reference period of a year is used to enable a more accurate sensing of the prevalence of own account and platform work, given the ad-hoc and transient nature of such work arrangements. Survey responses were mainly collected through internet submissions or telephone interviews. Where needed, face-to-face interviews were also conducted.

Implied operational definition

Platform workers in Singapore’s context refer to own account workers who provided paid labour services via online matching platforms. Such labour sharing platforms serve as intermediaries to match or connect buyers with workers who take up piecemeal or assignment-based work. These platforms could be either websites or mobile applications, covering services such as ride-hailing, goods/food delivery, creative work etc. Other types of platforms (e.g. capital-sharing or e-commerce platforms) are not included, as labour is not the main traded good in those cases.

Notwithstanding this, the survey separately captures a wider measure of own account workers who utilised any online channels to obtain business. Besides the aforementioned online matching platforms, this include (but not limited to) the use of e-commerce websites and social media platforms.

Some platform workers could be doing such work for their livelihood, while others do platform work on the side, e.g. multiple job holders with a full-time employee job, students, homemakers and retirees. Such a differentiation provides better insights to aid in more targeted policy interventions.

Singapore adopts the same definition of “employment” as that stipulated in the ILO resolution10 During the reference period, employed persons either

worked for one hour or more either for pay or profit; or (ii) have a job or business to return to but are temporarily absent because of illness, injury, breakdown of machinery at workplace, labour management dispute or other reasons.

worked for one hour or more either for pay or profit; or (ii) have a job or business to return to but are temporarily absent because of illness, injury, breakdown of machinery at workplace, labour management dispute or other reasons.To address the sporadic nature of own account or digital platform work, Singapore’s survey used a longer reference period of a year. In addition, the survey sieves out persons who did such work on a regular basis during the year, as such persons likely have higher work attachment.

Figure 5.6. Implied conceptual scope for Manpower Research and Statistics Department, Singapore study

The survey enabled a better understanding on the prevalence and nature of platform work in Singapore. At the most general level, the data show that, despite the emergence of online matching platforms, own account work has not displaced regular employment. The percentage engaged in own account work has remained fairly stable, at about 8% to 10% of all employed residents over the last decade.

With respect to digital platform employment per se, the latest 2020 survey found that about 3% or 73 500 of Singapore’s resident workforce was engaged in platform work as their primary job in the year. They were mainly involved in the transportation of goods and passengers. The majority engaged in platform work by choice, because of the flexibility and freedom they enjoy.

The top occupations in platform work were private-hire car drivers, taxi drivers, and car and light goods vehicle drivers. Work arrangements of platform workers can resemble those of employees. Platform companies often set the price of their product, determine the assignment of jobs to workers, and manage how the workers perform, including imposing penalties and suspensions.

Lessons learned

Platform workers’ contracts with platform companies are not employer-employee contract of services. This means platform workers do not have the statutory provisions that employees have, such as work injury compensation, union representation and mandatory social security contributions made by the employer. Because of this, the government is looking into strengthening protections for platform workers, specifically delivery workers, private-hire car drivers and taxi drivers, and ensuring a more balanced relationship between intermediary platform companies and platform workers. Singapore’s Prime Minister announced at the 2021 National Day Rally that an Advisory Committee will be convened to study this issue.

European Commission – Eurostat

Original purpose

In 2019 Eurostat launched a Task Force on Digital Platform Employment (DPE), with the purpose to answer to the increasing pressure for comparable information on gig/collaborative economy. Statistical measurement are of paramount importance to design informed policies and the main stakeholders are precisely the policy Directorates General of the European Commission. One of the goals provided in the Political guidelines for the European Commission 2019-2024, presented by President von der Leyen, is “improving the labour conditions of platform workers notably by focusing on skills and education”. EUaction is recognised as necessary in order to protect platform workers and reduce the risk of regulatory fragmentation across Member states.

The Task Force mandate has included the development of technical and methodological elements plus a set of variables/questions, which have been piloted in the EU-LFS within 2022 by the volunteered Member States to evaluate the results of this pilot exercise and to come with a revised proposal, in view of a full implementation in the EU-LFS. The pilot survey on DPE is ongoing and no results are available at present, but 2023 results will be used in terms of developing the final EU-LFS framework for the measurement, including the definitions of the phenomena. The implementation of DPE module within the EU-LFS for regular production depends on the pilot survey results and the final discussion taken by the Eurostat LAMAS LFS Working Group.

The technical/methodological proposal includes: defining the objective of the information to be collected, for example capturing additional persons in employment (as first or second job) who find work through platforms and/or having an overall number of platform workers; defining the labour market characteristics of interest of these platform workers: working conditions, professional status, quality of the work, required skills, etc.; defining the target phenomena (what are platform works? which platforms?); defining the reference population and the reference period.

Reference population and sampling

The reference population is all population within 15 and 64 years old, with respect to the population of the EU-LFS all persons aged 65 and more are excluded. Constraints to the survey are imposed by the EULFS nature. The focus should be on:

- the supply side of the labour market;

- the activities constituting employment (work for pay or profit, for more than one hour in a reference week);

- the counting of heads (not transactions, volumes or revenue);

- the activities where a website or an app plays an integral role in connecting workers to customers.

The main challenges are two: to identify the platform work within the employed people already detected in the LFS (as part of first or second job) and to identify employed people non-detected in the LFS who actually perform paid platform work.

The Task Force suggests that the pilot is asked to a sub-sample of the standard LFS (with the indication to be placed at the end of the questionnaire in order not to interfere in any way with the results of the current LFS). Dimension of the sub-sample should be at least, in each quarter of 2022, 1/10th of the national quarterly sample, in order to provide significant figures on the small phenomenon of the DPE. The information on actual sample size is not yet available when writing this Handbook.

Other relevant survey features

All features of the survey should be identical, or as similar as possible, to those of the EU-LFS, in order to produce comparable results.

Implied operational definition

The first step is to define “employment” in the context of DPE. This definition should remain into the LFS framework, implying that “employment” refers to the usual criteria: at least one hour of work for pay or profit in a reference week. Nevertheless, since the time horizon of a survey on DPE, being the DPE a rare phenomenon at the moment, cannot be the single LFS reference week, it has been decided to somehow extend the reference period of the pilot: the first set of questions refers to the last 12 months ending with the reference week of the LFS. Once the number of the DPE workers has been estimated the following sets of questions, on their characteristics, refer to the last month and to the reference week in order to make the link with the core LFS.

Consequently, the criteria for defining “employment” in the context of DPE is proposed to be:

To have worked for pay or profit in tasks/activities organised through an internet platform or a phone app, for at least one hour in at least one week, during the reference period.

Persons with very short spells of DPE work, specifically never spending more than one hour in one week for one year on paid work, are excluded, it may be the case of some micro-task workers. This should be a very rare phenomenon and its loss is compensated by the comparison advantage to link with the LFS definition of employment. Moreover this definition, while sticking on the LFS standard, enlarges the reference period to have more robust estimation.

Any task/activity that can be considered as “employment” in the LFS, i.e. production of goods or provision of services but also time spent in searching for clients or in setting up the working activity, should be considered as DPE when the other criteria are fulfilled. It includes in particular, work for pay and profit (1) for providing taxi or transport services including driving clients, delivery of food for restaurants, or transport or delivery of any kind of goods or similar, (2) for providing actual services in view of renting out a house, a room or any other accommodation, (3) for selling any good produced or bought with the intention of selling it online, and (4) for providing other kinds of services or work, among others: cleaning, handiwork, programming and coding, online support or checks for online content, translation, data or text entry, web or graphic design, medical services, creating contents such as videos or texts (with the purpose of earning money or other benefits).

For all tasks/activities listed here above, as far as the matching between the provider and the client is done throughout an internet platform or a phone app, the task/activity can be considered as DPE.

Concerning the definition of a “platform”, the OECD approach (based on work from the European Commission and others, used in its publication of March 2019 ‘Measuring the digital transformation: a roadmap for the future’) is followed:

An online platform is a digital service that facilitates interactions between two or more distinct but interdependent sets of users (whether firms of individuals) who interact through the service via the internet

Then, to define a work organised through a digital platform is necessary. It has been decided to take into consideration only work organisations involving three separate agents. On the vertex of the triangle are the three agents:

- The provider, in this context this is the supply side of the labour market and it is our target (the employed person);

- The client, in this context this is the demand side of the labour market (it may be an individual or a legal person);

- The platform: an internet platform or a phone app with the purpose to facilitate the match between the provider and the client.

It is important that the three agents are distinct. If the platform and the provider coincide, for example if the provider owns the platform like a producer that sells its goods on its own website, this is not anymore a triangular work organisation and the work cannot be classified as a DPE. Another example is the case in which the client and the platform coincide, the provider works through the platform owned by the client, as in case of teleworking. Again, this cannot be classified as DPE. Both examples show standard two agents relationships, while we are interested in new situations in which the market is characterised by the presence of a third agent. This can result in a smoother market where the platform plays a facilitation role in the matching of supply and demand, but also in market perturbed by the dominant position of the platform.

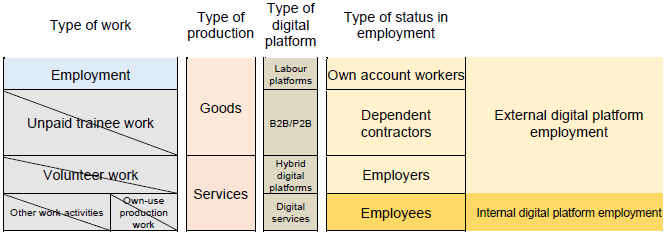

Figure 5.7. Implied conceptual scope for Eurostat study

It is also important that all three sides of the triangle represent an actual connection between vertexes. If the provider has no relationship with the client but only with (receive instructions, get paid, report to, etc.) the platform and the client also has only relationships (a commercial contract or other) with the platform, then there are two different traditional two-agent relationship instead of a triangular one. The decisions taken may exclude some kind of bilateral DPE, and this endanger the identification of some DPE workers in an employee position, but their number has been considered small with respect the high risk to improperly include many people simply in telework.

It has to be noted that for classifying a respondent in employment or not, the focus should be on the provider (i.e. the respondent); characteristics of the platform and of the client should not be taken into consideration. As far as the provider works for pay or profit, there is employment. Platform and client can be based in the country of interest or not, they can be individual or legal entities, etc. The provider must be resident in the country of interest and must be a person to be counted as “employed” or “not employed”. Obtained goals and learned lessons

The obtained goals, for the moments, cover only the set-up of the survey: the definitions and the way to include it in the regular LFS. No figures are currently available.

Information and Communications Technology (ICT) use survey

The ‘use of ICT’ survey is a household, or individual, survey aimed to investigate the diffusion and the trends in usage of new technologies such as the Internet or tools such as computers11. Information needs to be covered are, among others:

- access to and use of ICTs (including tools: computers, mobile phones, others)

- use of the internet and other electronic networks for different purposes (e-commerce for example), • ICT security and trust,

- ICT competence and skills.

Focusing on the individuals it covers the supply side, the DPE worker point of view, and the client side, when the client are individuals, such in case of food delivery or taxi services. It may be difficult to distinguish the provider and the client, both answering that they use the platforms. Survey designers should put attention on clearly wording the questions, especially when the data collection mode is web based, with no help from an interviewer. A section on DPE should be explicitly provided and ad-hoc designed, among the other information sections of the survey.

It can cover the DPE not covered by the LFS, for example for very occasional providers, which do not even consider themselves as in employment, and can be useful to investigate particular aspects such as the skills of the providers and details on time spent on the platforms.

Canadian Internet Use Survey - Statistics Canada

Original purpose

The 2018 and 2020 Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS) covered digital labour platform work through its module on online work. Among other things, the module aimed to capture participation, activities and money earned from online work. There was the possibility of getting some information on the features of the platform workers through questions on education, Aboriginal identify, and other labour market activities.

In CIUS 2018, a filter question asked about whether the respondent had used the Internet to earn income in the previous 12 months. For those who did, a follow-up question asked about whether the income earned was the main source of income or an additional source of income. Finally, a third question asked the method through which the income was earned, with respondents having to choose between seven categories. Each category included examples of platforms used for earning income online.

The full list of the methods to earn money on the internet were the following:

- online bulletin board for physical goods (e.g., Etsy, Kijiji, Ebay);

- online bulletin board for services (e.g., Kijiji, Craigslist);

- platform-based peer-to-peer services (e.g., Uber, Airbnb, AskforTask);

- online freelancing (e.g., Upwork, Freelancer, Catalant, Proz, Fiverr);

- crowd-based microwork (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk, Cloudflower);

- advertisement-based income (e.g., income earned through YouTube or personal blogs);

- other.

In 2020, the questions about activities to earn money online were asked differently, with each type of activities presented as a separate question. Nine types of activities done online to earn money were presented, compared to seven in 2018.12

Reference population and sampling

The target population of the CIUS was all persons 15 years of age and older living in the ten provinces of Canada. It excluded full-time residents of institutions.

Figure 5.8. Implied conceptual scope for Statistics Canada study