- 3.1 How can PES offer job search assistance?

- 3.2 What services can PES provide to improve jobseekers’ employability and help to prepare them for work?

- 3.3 Why is it important to provide support with job search techniques?

- 3.4 What services can PES offer to help jobseekers to develop work-related soft skills, or to allow them to reskill or upskill?

- 3.5 What role do PES have in providing career guidance?

- 3.6 How can PES support the transition from informal to formal employment?

One of PES’ main roles is, and will continue to be, matching jobseekers to enterprises. However, rather than placing jobseekers into any job the goal is to place jobseekers into suitable work that best matches their skills and it allows the jobseeker to create a sustainable career going forward. By investing in services for jobseekers, PES can ensure efficient and effective matching processes with enterprises hiring individuals with the right skills that fit their needs. Services to jobseekers can also assist workers’ transitions from: u Work to work;

- School to work;

- Unemployment to work;

- From the informal to formal economy;

- Precarious employment to sustainable, high-quality employment; and

- Providing caring responsibilities to employment.

This means that many PES are increasingly investing in creating services that are suitable for all types of jobseekers, regardless of their labour market status. In the long term, this can contribute to positive perceptions of PES and thus enhancing the reputation of PES.

The table below provides an overview of the people, processes and services involved in delivering services for jobseekers and wider support services to help people fulfil their potential.

Table 3.1 Supporting people to fulfil their potential: PES staff, process and services

| PES staff | Processes | Services |

| Frontline counsellors | Initial assessment | Individual action plan |

| Middle-managers | Profiling of jobseekers | Pre-employment training provision |

| Matching process | Online vacancy platform | |

| Staff training | Career guidance |

This section will provide information on how PES can add value, upgrade and further develop support services for jobseekers. Such services can contribute towards a better, more efficient matching process and, consequently, to reduce the likelihood of jobseekers returning to PES after a short time.

3.1 How can PES offer job search assistance?

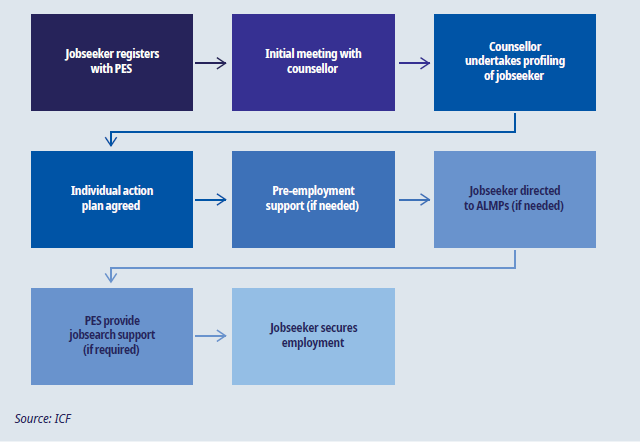

Providing jobseekers with assistance while searching for jobs is the first step in helping an individual to secure suitable employment. This is a large part of the core services that PES offer for jobseekers. How jobseekers look for jobs and the nature of job search assistance has evolved over the last 10 years with the advent of digital services as certain types of jobseekers (i.e., those who are IT literate and have reliable access to the Internet) have increasingly become self-sufficient and this means that the types of jobseekers that frontline PES counsellors are dealing with are often facing multiple barriers to employment. Going forward, job search assistance and services to jobseekers as a whole will move towards being a very individualised service, tailored specifiс cally to each individual’s needs. The customer of such services will likely become much wider than unemployed jobseekers in the future as it is likely to move towards covering some of the following groups:

- Individuals making work-to-work transitions;

- Individuals making school-to-work transitions;

- Individuals at risk of redundancies;

- Those looking to relocate (for example, making rural to urban transitions); and

- Migrants

- .

Figure 3.1 Jobseeker workflow from registration to employment

3.1.1 What is the role of online services in individuals’ job search?

Digital services are one of the most important components for jobseekers as it allows them to take forward their job search on their own, at times that suit them and wherever it suits them. When referring to digital services, it is meant that jobseekers will be able to find information about the labour market and vacancies (as a minimum). Having such services in place enables a quicker and more efficient matching process as less jobseekers will require one-to-one time with an employment counsellor as they have found employment by themselves.

A pre-requisite for online services is that they must be user-friendly, easy to search and to have up-todate information available. This implies that PES have the digital infrastructure in place to automatically upload vacancies, develop beta testing sites as well as frameworks for collecting and protecting personal information that may be gathered by online portals.

Digital job search assistance tools, such as vacancy portals and skills assessment tools, can rely on jobseekers being IT-literate and having reliable access to the Internet. In addition, such services require jobseekers to use their initiative and self-manage and take responsibility for their own job search activities. This means that such services will not be appropriate for some types of jobseekers and this can lead to a change in the type of jobseekers that require assistance from PES frontline counsellors. These jobseekers are more likely to lack IT skills and/or access to the Internet and are likely to be those furthest from the labour market. As a result, they will require more assistance from frontline counsellors to find suitable employment and this can have implications for the organisation and management of PES resources.

Case Study 2. Online job search platforms in Russia

ROSTRUD have developed two online platforms to facilitate the matching process between jobseekers and enterprises.

Firstly, ‘Work in Russia’29 is an online platform where enterprises can add vacancies and jobseekers can add their CVs and search for vacancies. This can be done by key words, salary, type of employment, sector and required years of experience. Jobseekers can also take an online ‘quiz’ to find out what types of careers best match their interest and skills and they can also view information on the employment landscape in different regions of Russia.

Secondly, Skillsnet.ru30 was developed by ROSTRUD to help jobseekers to engage with enterprises. Jobseekers are able to upload their profile and add their experiences and skills which will help them to assess their own competencies and help them to consider what types of employment they are most suited for. The platform also provides thematic groups where jobseekers can choose to receive notifications on relevant topics and discuss specific points with other jobseekers and professionals. In addition, jobseekers can view reviews on enterprises by current or previous employees and this can help them find out more about the positions available and the working environment.

3.1.2 How can profiling jobseekers support future similar jobseekers?

Profiling is the assessment undertaken by PES counsellors and can include using IT and statistical tools to personalise PES services.2 This approach can help to make the labour market integration jobseekers more efficient and effective as PES counsellors can better target services according to the needs of jobseekers and limited resources can be better utilised. Within PES, profiling tools are typically used to3:

- Identify the assets and difficulties of a young person with a view to developing a personalised employment and/or education and training action plan;

- Anticipate the risk of joblessness of a young person who is about to enter the labour market, or is unemployed;

- Assess the level of support that is required to overcome the difficulties and make a successful labour market transition;

- Target services, measures and programmes considered most suitable to meet the requirements of each particular “profile”;

- Match jobseekers to vacancies; and

- Allocate resources for the assistance of individuals most at risk in the labour market.

This can allow frontline counsellors to see what has worked for other jobseekers with similar characteristics in the past and provide targeted support and guidance. For example, profiling can identify that groups of jobseekers have required specific training before entering employment in certain sectors. Counsellors can use this information to shape the information and guidance they provide to jobseekers.

Profiling allows PES to collect data on jobseekers and over time to aggregate this data and make comparisons with others with similar characteristics (e.g., age, education, experience level and so on).

Profiling requires good IT infrastructure in place so that jobseekers’ data can be systemically collected as part of the jobseeker registration process on a local, regional and national basis. This information also needs to be analysed on a timely basis and shared in an easy-to-understand way with counsellors. This is important so that counsellors can provide up-to-date information to jobseekers and their advice and guidance can incorporate any emerging trends or developments in the local, regional or national labour market. An important aspect to the success of profiling methodologies is the need to provide staff, such as frontline counsellors, with relevant training to inform them of the purpose behind profiling, introduce them to the methodologies and how to use any new systems.

The following sections will introduce two profiling methodologies: skills-based profiling and face-to-face/ digital services for initial profiling.

In order to put skill needs systems in place, PES need to take an ‘anticipation’ approach and put relevant procedures in place, working with ministries and other partners to do so. Anticipation of skills needs aims to identify:

- relationships between skills supply and demand; and

- emerging skill and labour requirements in a country, sector or region, as a result of new labour market conditions, technologies or organisational changes.4

3.1.2.1 Using skills-based profiling to find out the skills individuals possess

Matching brings supply and demand together as well as filling jobs with well qualified individuals. Labour market intelligence systems (see Section 3.2.6 to find out more) can help PES to look forward to see the skills and demands that will likely be required in the future labour market. PES have an important role in matching and skills profiling as they can work together with labour market authorities, education and training authorities to:

The table below provides an overview of the different actors who may find it useful to have information about skills of current and potential jobseekers.

Table 3.2 Who should be provided with information about skills demands?

| Type of actor | Reason |

| PES counsellors | They can use information about skills in demand to deliver more targeted advice and guidance |

| Individual jobseekers | They can assess their own skills against those required by the labour market and they can take any actions to highlight their skills, or to develop new skills |

| Training providers | They can adjust training courses to meet new and emerging skill needs |

| Education providers | They can provide guidance to their students as to what areas to study and what qualifications are in demand |

Source: ILO, ETF and Cedefop (2015) ‘The role of employment service providers: guide to anticipating and matching skills and jobs‘

Data collection can be integrated into registration processes and provide counsellors, jobseekers and employers with ‘real-time’ information on the local, regional and national labour market. If such advanced tools do not exist, PES can still collect data on a regular basis and share their findings with other stakeholders, such as education and training providers.6

Skills-based profiling looks at jobseekers’ skills and competencies to identify strengths and areas of development for individuals. It can help to determine individuals’ transferable skills that can help them with their job search and to identify gaps in their skills that need to be addressed before they enter employment.

Increasingly, some PES are using skills-based profiling to find out more about individual jobseekers’ skills, including soft skills and transferable skills. This can also help to find out more about jobseekers’ levels of self-awareness, self-confidence and their potential. The results of skills-based exercises, such as psychometric testing and other similar tests to collect and record jobseekers’ skills, can help jobseekers’ to realise their strengths and help them and frontline counsellors to identify their skills gaps and potential next steps. Such activities can be considered as empowering jobseekers as this can give them knowledge of their strengths and skill sets that can help them to move between jobs, occupations, and sectors, with important implications in terms of the quality of matching (as described above).

This approach to profiling can be argued as being a more suitable profiling methodology within the future world of work context. Section 2 outlined how the labour market is adapting to technological developments and globalisation which mean that labour markets tend to transient and local labour markets will change and evolve over time. Therefore, jobseekers’ may not work in a specific sector for their whole life and their transferable skill sets become important to enable them to make rapid work-to-work and unemploymentto-work transitions.

3.1.2.2 Registration and initial profiling can be done face to face or via digital services

Registration of jobseekers and initial profiling can be done either face to face or via online, digital services. This approach varies across different countries and it can be affected by:

- Registration requirements

- Extent of online, digital services

- Type of jobseeker

The registration requirements for jobseekers may differ from country to country. For example, jobseekers may be required to provide a signature, and this could be either provided electronically as part of an online registration or in person. In addition, jobseekers may be required to provide original documents to proof their income, name and address. Online registration systems may provide options for such documentation to be uploaded however some countries may require hard copies, viewed and ‘approved’ by a PES member of staff .

Where online, digital services are developed there can be opportunities for initial profiling to be built in. This can provide jobseekers with an opportunity to complete fields such as their age, education, employment history and other areas. This can provide counsellors with an initial profile for each jobseeker and the results of which can be fed into an initial meeting between the counsellor and the jobseeker. Online initial profiling may help to get counsellors up to date with the profile of each jobseeker and reduce the time needed for this activity in a face-to-face situation.

However, it is important to remember that the type of jobseeker is an important factor in determining the registration and initial profiling methodology. For example, some types of jobseekers (such as those furthest from the labour market, or older workers) may not find online registration or initial profiling systems useful as they may lack IT skills and online access. Therefore, if online registration and profiling is offered it is important to keep a face-to-face option to enable accessibility for all.

An important feature of services for jobseekers that should be done face to face is the agreement of an individual action plan (outlined in more detail below). This enables the counsellor and jobseeker to have an in-depth two-way conversation that explores the future employment prospects, plans and steps required for each individual jobseeker and it is much more likely to get greater insights and inputs from the jobseeker at this stage. This is useful when tailoring job search support services to each jobseeker.

3.1.3 How can individual action plans be designed, developed and used?

Individual action plans can be an important tool for PES to provide a personalised, client-centred effective approach to help the (re-)integration of jobseekers into the labour market. Individual action plans are agreement that developed between a PES counsellor and an individual jobseeker that outline key actions for the jobseeker that they will undertake, and the PES will do to help them gain employment in the future. This can include job search activities, work preparation activities (such as workshops) and undertaking any additional training as required.

In many PES individual action plans are introduced to jobseekers at the first meeting between the jobseeker and counsellor. The individual action plan outlines an agreed path of actions that will help the jobseeker to achieve employment. This provides the jobseeker with an opportunity to critically refl ect on what steps they would like to take towards employment. By doing this, jobseekers can develop a sense of self-awareness, responsibility and motivation for undertaking the agreed activities in their job search. Box 6 below outlines the key features of individual action plans.

Box 6. Key features of individual action plans

The following points are important aspects of individual action plans:7

- Summary of the individual’s assessment by the counsellor, including relevant profiling results (where profiling has taken place);

- Goals (or objectives) agreed between the counsellor and jobseeker;

- Agreed steps that the jobseeker will take towards the goals; this can include ALMPs and other measures that are available and relevant to the jobseeker;

- The duties and commitments of the counsellor (and PES) and the jobseeker (e.g., stating how often they will meet face to face);

- The rights of the jobseeker;

- Rules and procedures concerning the application of sanctions;

- Information on the complaints and appeals procedure; and

- The individual action plan – all of agreed steps at a glance.

Individual action plans are an important vehicle to personalise PES services and approaches to the precise needs of individual jobseekers. This helps to make services much more client centred as individual action plans outline tailored pathways to each jobseeker. This can contribute to more efficient services and activities by targeted activities such as ALMPs and other measures towards those whom would benefit most from them. Their success depends on the interaction between counsellors and jobseekers therefore relevant training for counsellors is important so that they have the right skills, knowledge and competences to help jobseekers identify their goals, objectives and steps towards employment.

Individual action plans should be ‘live’ documents that are referred to on an on-going basis. For example, they can be referred to during each face-to-face meeting between a jobseeker and counsellor as a basis for the discussion. By reviewing the individual action plan during each meeting, the jobseeker is reminded of their agreed actions and the counsellor can review progress as well as any additional actions.

3.2 What services can PES provide to improve jobseekers’ employability and help to prepare them for work?

As part of a good quality offer to jobseekers, PES should deliver a range of services that help jobseekers to improve their employability and help to prepare them for the world of work. This support can help jobseekers make sustainable transitions from unemployment to work and, increasingly, work-to-work transitions. Such services should be offered to jobseekers on the basis of their individual needs (as identified via any profiling) as well as in line with the agreed steps included in the individual action plan.

Services to improve employability and preparing jobseekers for work tend to focus on providing jobseekers with information and assistance on job search techniques, work-related soft skills, work-related behaviours and expectations and they can cover second-chance education and training for young people.

Figure 3.2 Different types of employability and work-preparation services

Services around improving employability can be delivered in three different ways:

- Collective services (e.g., to a group of people, who can be known or not known to each other).

- Targeted group services (e.g., to specific groups, such as early school leavers, or those at risk of dropping out of education).

- Individualised services.

The audience and number of participants for each employability service depend on their intended aim and objectives.

The table below outlines some specific examples of services and programmes that PES can use to improve jobseekers’ employability and help to prepare them for work.

Table 3.3 Examples of PES programmes and services

| PES programmes and services | What are they | Potential target audience (jobseekers) |

| Entrepreneurship schemes | Entrepreneurship schemes can provide specific target groups with financial support and advice for a fixed amount of time to develop a business idea and establish a business. |

|

| Second chance programmes | These programmes target individuals who have missed out on labour market opportunities. They can include counselling, training, employment subsidies and other forms of support and assistance. |

|

| Wage subsidies | Wage subsidies can encourage enterprises to hire specific groups of jobseekers, whom may be harder to place or who have little experience. They can either provide a tax reduction, vouchers or a financial grant for enterprises. |

|

| Work experience programmes | These aim to provide individuals with paid or unpaid work experience in a public or private sector enterprise. They can include internships organised by education institutions for their students. |

|

| Youth Guarantee | A Youth Guarantee provides a young person with a right to a job, training or education. PES or other employment bodies have an obligation to provide an offer within a set period. |

|

3.2.1 What skills are needed by PES staff who work with jobseekers?

PES staff who are working with jobseekers need to have some specific competences, which differ to the competences required by other PES staff (e.g., PES staff who work with employers). This is so that staff are best placed to provide appropriate services and support to jobseekers and PES resources can be efficiently used. The table below outlines the key competences and behavioural indicators, developed by the European Commission, which may be a useful source of inspiration and information for PES in the region when thinking about the skill set of PES counsellors who work with jobseekers.

Table 3.4 Key competences and behaviours of staff working with jobseekers

| Specific skill | Key competences | Key behavioural indicators |

| Practical knowledge of individual action planning including promotion of career management skills /employability | Ability to set up and monitor implementation of an Individual Action Plan (IAP) with a view to enhancing career management skills |

|

| Counselling: patience, understanding and the ability to listen non-judgmentally | Ability to retain emphatic and supportive attitude towards clients, patience and understanding, even when faced with complex problems or resistance |

|

| Ability to motivate clients | Ability to motivate, inspire and support clients by developing productive interactions |

|

| Ability to conduct resource-oriented assessment | Ability to analyse the characteristics and needs of the jobseeker with the use of adequate assessment tools and techniques |

|

| Problem solving skills | Ability to analyse and structure the problem, identify and consider possible options, make decisions and resolve difficulties |

|

| Ability to make justified referrals to appropriate measure | Ability to make effective referrals to an appropriate measure or provider on the basis of individual client assessment, availability of support and effectiveness criteria |

|

| Assessment and matching skills for job placement | Ability to sequence a job placement process by matching job requirements with the outcome of individual assessments |

|

| Information finding and analysis skills | Ability to identify, find, analyse, combine and interpret information which is important in facilitating the placement process |

|

| Human resources management knowledge | Application of human resources management concepts for quality placement processes |

|

European Commission (2014) ‘European reference competence profile for PES and EURES counsellors’

3.3 Why is it important to provide support with job search techniques?

Undertaking a job search is a fundamental step in finding suitable employment. Knowing how to do this and how to do this well is essential knowledge for all jobseekers. However, some jobseekers may not have the right knowledge to do this or may not have had experience of looking for jobs in the past. The PES therefore has an important role in providing information and assistance to jobseekers to develop or refine their job search skills and techniques. This can include different aspects of the job search process, such as how to write a good CV and interview techniques.

Workshops focusing on CV writing and interviewing techniques can be undertaken in medium sized groups, or specific groups of jobseekers. They can include basic information about the approach, tailored to the needs to the nature of the group, as well as interactive exercises for the jobseekers to undertake to apply their learning and (where possible) gain feedback from workshop leaders.

Such workshops can be delivered by PES staff , or specialist providers, who can offer jobseekers with valuable insights as to what makes a well-written CV, key aspects for successful interview techniques and common errors.

Workshops around job search techniques should be available to jobseekers year-round and on regular basis (for example, on a weekly basis) as part of the standard PES service offer. It is important to also complement the information provided during the workshops with an accessible information source that participants can consult afterwards if needed. This can be via hard copy handouts but importantly, useful information should also be offered as part of PES websites around job search techniques. PES may wish to work with specialist providers to provide this type of content, so that jobseekers can access clear and easy-to-understand information and advice on job search techniques. By having this type of information available online, jobseekers who participate in workshops can access this at any time as well as other jobseekers who may not attend such workshops. In addition, having job search information available online opens up the possibility of jobseekers (who have not registered with PES) to access PES resources.

In terms of who should attend such workshops, counsellors can recommend job search technique workshops to jobseekers whom they consider as most in need to develop or refresh their skills in this area. If individual action plans are used, counsellors can include attendance to job search technique workshops as an action for an individual jobseeker. In addition, PES can target specific groups of jobseekers who may be in a position to benefit from this service, such as older workers and young unemployed people, who may have had limited experience of looking for jobs in the past. In addition, counsellors can also refer individuals to attend workshops if they have been unemployed for some time (for example, more than six months) and therefore could benefi t from refreshing their knowledge in this specific area.

Offering such services is important for PES as it can help to facilitate and improve the efficiency of the matching process. Jobseekers who have attended job search workshops may be able to put forward better prepared CVs and may have better interview techniques compared to if they had not attended such workshops. This means that enterprises may be more likely to hire such candidates and therefore may be more likely to hire a jobseeker referred by PES in the future. Jobseekers also benefit as they can gain lifelong skills that can help them with future job searches, which may reduce the risk of them returning to the PES in the future.

3.4 What services can PES offer to help jobseekers to develop work-related soft skills, or to allow them to reskill or upskill?

Some jobseekers may not be ready to go directly into employment and may need additional support to improve their soft skills, or to reskill or upskill with a view of developing skills that are appropriate to the current labour market needs.

Support that focuses on developing work-related soft skills may be suitable for those furthest away from the labour market, for example long-term unemployed, young people who have dropped out of education or other disadvantaged groups who are facing multiple barriers into work.

Soft skills can include things like communication, teamwork, interpersonal skills and flexibility/ adaptability to new situations.

By providing jobseekers with opportunities to develop their work-related soft skills, as well as opportunities to improve their literacy, digital and numerical skills, PES are providing jobseekers with life-long skills that help develop individuals’ skills sets so that they are better equipped to make the transition into employment.

In comparison, support services around reskilling and upskilling can target older workers who are transitioning in the labour market due to changes in their jobs, or sector. However, such services can also be deployed in cases where large companies (e.g., in the manufacturing sector) are relocating and thus a group of skilled workers need to upskill or reskill so that they have an appropriate skill set to the needs of the local labour market.

In both cases, workshops available to targeted groups or collective services can be a suitable mechanism to deliver training around work-related soft skills and upskilling and reskilling workshops. PES may find it beneficial to work with selected partners, such as sector-specific training providers or local education institutions to deliver such workshops. Such workshops should be scheduled at times that are mindful of their intended target groups. For example, workshops for those in work but looking to reskill and upskill should be delivered in evenings or weekends and workshops for young people may not be suitable to be delivered early in the morning.

3.4.1 How can PES prepare jobseekers for work-related behaviours?

Work-related behaviours include professionalism, punctuality, ability to act responsibility and able to meet deadlines. These are important behaviours for employees to demonstrate in work however some jobseekers (such as the long-term unemployed) may not possess them and therefore need to be trained on them before they gain sustainable employment. By investing in such training, PES reduce the risk of jobseekers quickly leaving employment or being dismissed by an enterprise as they have failed to demonstrate these core competences.

Work-based learning is learning that includes the process of undertaking and refl ecting on productive work in real workplaces, paid or unpaid, and which may or may not lead to formal certification. It provides individuals with exposure to real work environments (or simulated work environments) and it provides opportunities to develop knowledge and practical skills.8

One method that is used successfully by PES across the region to prepare jobseekers for work-related behaviours is work-based learning. This provides jobseekers with an opportunity to learn a specific skill, or range of skills, as well as developing work-related behaviours.

Work-based learning is known by different names and it can include apprenticeships, traineeships, work placements, work experience and internships. It provides an opportunity for individuals to develop workrelated knowledge as well as an opportunity to develop and put into practice work-related behaviours, such as turning up on time, communication skills, team working skills and professionalism. It also allows individuals to learn other skills and behaviours as well that can strengthen their transitions into the labour market.

An important aspect of delivering work-based learning programmes is establishing working relationships with an extensive network of enterprises, who may be willing to provide placements for individuals, work trials or even a member of staff to oversee and provide input into simulated working environments. In addition, it may also be helpful for PES to establish good working relationships with vocational education training providers so that simulated working environments can be provided as well and PES can benefit from their knowledge of providing work-based learning activities. PES may also wish to subcontract specific services to training providers to deliver work-based learning activities, which would ensure that highly, relevant skilled individuals are responsible for such programmes and this can be a more efficient use of PES resources.

Across the world, programmes that include work-based learning have facilitated transitions to decent, sustainable work and have proved to lead to stronger and better labour market outcomes for individuals, enterprises and governments. This is in terms of better employment outcomes and wages, and positive rates on return on investment to enterprises and governments.9

3.4.2 What is the role of second chance education and training programmes?

Young people who are unable to finish education and training programmes are at a disadvantage in the labour market as they do not have relevant qualifications or skills, knowledge and competences that enterprises are looking for. So called ‘second chance’ education and training programmes are designed to provide young people who have been unable to complete their studies with an alternative route and help young people to make the transition from unemployment to employment. Second chance education and training programmes can help to address the root causes of their failure and they offer motivating environments for learning.10

By providing young people with an opportunity to develop new skills, knowledge and competences, they will also become more attractive to enterprises and thus be in a better position to find suitable employment in the short-term and longer-term.

The table below identifies the key elements of successful second chance education and training programmes.

Table 3.5 Key elements of successful second chance education and training programmes

| Element | In place? |

| One to one with programme leader/tutor and participant where their learning needs, gaps in knowledge and training and other support needs are identified and agreed in an individual development programme |  |

| The programme includes practical training |  |

| The programme is delivered in small classes in a supportive, motivating environment |  |

| The programme combines practical training with short-term work experience placements |  |

| Participants can access psychological and other support (e.g., a mentor), so that other external issues and obstacles to labour market participation can be addressed |  |

Source: ILO (2017) ‘Towards policies tackling current youth employment challenges in Eastern Europe and Central Asia’

Second chance education and training programmes can be used as a ‘preventative’ measure for those at risk of being not in education, employment or training (NEETs). This approach requires working closely with schools to identify at-risk young people and provide them with additional support and alternative forms of education and training. This introduces PES services to at-risk young people at an early age and helps to maintain contact with the young person as they make the transition from education to employment.

These types of programmes tend to be very personalised to the specific needs and wishes of each participant as this helps to maintain their engagement as well as work around any external barriers that they may be facing. In addition, successful second chance education and training programmes tend to include on-going counselling from one named contact at the PES. This is so that trust can be built up between the young person and PES staff and so that the PES counsellor is fully aware of the young person’s specific needs and any barriers that they are facing.

Young people can either be identified by schools or other types of partners (such as social services, youth organisations) as potential beneficiaries (a ‘proactive’ approach) or they can be referred to such programmes when the young person themselves register with the PES (a ‘reactive’ approach). A proactive approach means that PES need to take the initiative to work with different partners, such as schools, to work with young people who are deemed as being at-risk of dropping out of education. This can be facilitated by a PES member of staff visiting the school and having meetings with young people identified as being at risk as this can heighten the profile and services of PES to young people as well as providing PES with in-depth knowledge of the issues that at-risk young people are facing. Case Study 3 below outlines an approach taken by the Norwegian PES regarding identifying at risk young people and offering second-chance education and training programmes.

Case Study 3. Norway: PES tutors in upper secondary schools: working together with schools to reduce dropout rates

In Norway, a pilot took place between 2013 and 2016 to bring PES and schools closer together to provide counselling and support to young people at risk of leaving upper secondary education. PES tutors were based within schools to work with teachers and students, aged between 15 and 21, to reduce the risk of them leaving education and to help them integrate into the labour market. The pilot project also trialled cross-sectoral collaboration, developed knowledge about the need for and use of PES services for young people and deepened the PES’ knowledge about the issues facing young people.

PES tutors provided practical support to young people who were facing complex challenges (such as mental health issues or social problems); signposted young people to PES services and facilitated work experience, where relevant. They also provided specific support classes for the most disengaged students.

Through the pilot project, 45 PES tutors from 33 PES offices were integrated into 28 upper secondary schools’ student support services across Norway. The pilot led to greater knowledge between both parties and the partnership was essential in keeping track of young people making the transition between education and employment. An essential aspect of the success of this project was the buyin of all actors from ministry level to frontline staff and the involvement of all stakeholders from the start.

Since the end of the pilot project in 2016, the work has been rolled out nationally as part of ‘Career Guidance Partnerships’. The mandate was increased to cover career guidance to adults and online career guidance services.11

Another important element to having young people referred to second chance programmes by other types of partners is having agreements around the exchange of data. This includes any information that the partner holds on the young person, such as:

- Contact details

- Date of birth

- Education history

- Previous employment

- Any other studies or work-based learning experiences

Data exchange arrangements may depend on local legislation however if legislation prevents this from taking place automatically, organisations can ask each young person to sign a consent form that explains why their data may be shared with a partner and what data will be shared and for each participant to confirm that they are happy for their data to be shared.

The topic and nature of second chance training programmes often vary according to the target group, their specific needs and any specific requirements of the local labour market. These points must be factored into their design and delivery so that they are relevant, tailored and create the conditions for participants to succeed. They can include fast-track, intensive education programmes that provide participants with an opportunity to gain a qualification in a shortened time period. These types of second chance programmes are often delivered in smaller groups where tutors are able to provide more intensive learning support and participants may receive additional support in parallel, needs-dependent. In some cases, a range of different pedagogical methodologies can be used as traditional teaching methodologies may not be suitable for the needs of the target group. A mix of different pedagogical approaches may also be much more engaging for the target group as well, thus helping to create a different environment to traditional education experiences.

Providing education and training programmes such as these as well and providing specialised support to participants (particularly young people) can require additional resources and expertise from PES staff . Firstly, in terms of expertise PES who are dealing with young people may need to have slightly different skills to a traditional PES counsellor. This is because they need to be able to engage with young people in language that young people understand and if they are undertaking proactive work like visiting schools, youth organisations or others then they need to be able to have good interpersonal and networking skills. In addition, PES who work with those likely to enter second chance programmes may need to take on a lower caseload as these individuals are likely to require a greater level of support.

Secondly, the delivery of second chance education and training programmes can be quite specialised in terms of content as well as the skills required to deliver them. If PES do not have the capacity or the skills and expertise to deliver these programmes, then they can work with specialist providers to deliver specific services. This can offer the advantage of releasing valuable resources for PES as well as using service provider to deliver specific services and thus delivering the highest quality services possible. Case Study 4 (below) provides an example of how European PES are working with other partners to deliver individualised offers to young people who are not in education, employment or training.

Case Study 4. European Youth Guarantee Scheme12

The European Youth Guarantee is a commitment by all Member States to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 years receive a good quality offer of employment, education, apprenticeship or traineeship within a period of four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education. PES have an important role in this by working with partners to develop outreach and activation activities to young people.

Outreach activities refer to activities that organisations do to proactively reach out and engage with young people. For example, this could be youth workers physically going to places where young people meet and talking to them to gain their trust.

Activation activities refer to activities that help to get young people ready for re-entering employment, education or training. For example, this could be supporting them to successfully complete a second-chance education training programme or other pre-employment preparation training.

Within five years of the Youth Guarantee being in place, there is:

- Across Europe, 2.3 million fewer young unemployed people and 1.8 million fewer young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs);

- A decrease in youth unemployment from a peak of 24% in 2013 to 14% in 2019; and

- A decrease in the share of 15 to 24-year olds not in employment, education or training, from 13.2% in 2012 to 10.3% in 2018.

The European Youth Guarantee scheme has inspired other countries to develop similar Youth Guarantees and this idea is now being taken forward in South Africa. Other non-EU countries that are considering implementing components of the YG are South Korea, New Zealand, the Gulf Region and Ghana.

3.5 What role do PES have in providing career guidance?

The ILO ‘Work for a brighter future: Global Commission on the Future Work report13

calls on governments to invest in PES so that they are better equipped to support people through increasing labour market transitions and better prepare workers for transitions. PES therefore have role in providing career guidance that helps people to build sustainable, agile careers from school age to retirement. PES are uniquely positioned to do this as they have expertise in terms of providing counselling services. They also have in-depth information on labour market needs, future recruitment trends and sectors that are in decline.

By providing career guidance and professional orientations, PES can better equip jobseekers as well as employees to make multiple transitions during the working life and empower them to build a successful career. This helps PES in terms of reducing the likelihood of jobseekers returning to PES in short succession and it can contribute to enhancing PES’ role and profile within the labour market.

To do this, PES can either deliver it themselves and they can also work with different partners to provide assistance via one-stop-shops. One-stop-shops use cross-sector partnerships to deliver services in a coordinated way. This can help to tackle reputational issues that PES face in the eyes of the public (and especially young people). Case Study 1 in Section 2.2.5 provides an example of how the Finnish PES has worked in partnerships to deliver career guidance via a one-stop-shop to young people.

If considering a one-stop-shop model, ensure that the key inputs and outcomes of the services are jointly agreed between partners, seek evidence to support the change and evaluate to ensure service provision continue to meet the needs of the target group.14

Career guidance is primarily aimed towards assisting two transitions between school and work, and work and work. The following sections will focus on the provision of career guidance together with schools to target young people in order to assist them with school to work transitions and how PES can provide ongoing career guidance to support work-to-work transitions.

3.5.1 Who can PES work with to target young people?

PES can work with schools to provide tailored career guidance to young people, including at-risk young people, before they leave full-time education so that they can make better informed decisions about their working life. Providing ‘preventative’ support to young people can reduce the likelihood of them accessing PES core services in the future and they are well prepared for making the transition to employment.

To do this, PES need to establish good working relationships with schools and any other bodies who may be providing career guidance. In practice, PES can visit schools or groups of schools to highlight PES services with staff and, ideally, make arrangements for a member of PES staff to visit school(s) on a regular basis. This offers the advantage of schools being able to learn more about labour market needs, which can help them to prepare their students more widely for the world of work. In contrast, PES can find out useful intelligence about young people, for example the information that they need and their understanding about their career prospects. In addition, such collaborations can enhance the reputation of PES with young people, which may increase their likelihood of seeing the PES in a positive light in the future, and this will also enhance PES’ reputation with schools as they see the PES as an expert on the labour market and more than just a labour exchange.

Career guidance provided via schools should cover different aspects of the labour market in addition to job search techniques in order to prepare young people fully for the school-to-work transitions. Targeting young people early (i.e., before the transition to employment) is important to make them aware of the realities of the world of work and help to equip them. This can be via providing young people with information on labour market needs and trends; providing realistic guidance based on labour market trends; advising and supporting young people with job search techniques; and providing support in suitable spaces. These four key factors are explained in more detail below:

- PES should provide schools and young people with information on labour market trends. This is important to provide young people with an overview of what sectors are prevalent in a local area and consequently what skills they may need to enter employment within these sectors. In addition, PES may have insights into which sectors and enterprises are likely to hire, or are likely to decline, in the coming years. This can help young people to make informed decisions around what further education and training they may need to help them position themselves for employment in certain sectors. This can be delivered in the form of presentations, careers fairs as well as visits.

- Based on this labour market information PES are well positioned to provide young people with realistic solutions to their individual hopes around their future careers. Often young people have unrealistic expectations about their future career and in some cases they may take forward training and employment to help them to achieve these dreams but by receiving realistic, informed career guidance from PES then they will be better prepared to make a realistic career plan, based on the current (and projected) labour market needs. This can also include information on male-dominated profession and sectors as well as how females can navigate such bias, for example by promoting any relevant active labour market programmes.

- PES should provide young people with information on job search techniques so that they have the information at an early stage. This can cover how to look for jobs, how to apply for jobs, building a CV as well as providing information on interview techniques. Such information can be shared via workshops in schools or escorted group trips to PES. By providing young people with this practical information, PES are passing on vital skills to young people that they can start to apply straight away in their transition to employment.

- When providing career guidance to young people, PES need to consider the creation of suitable spaces. For example, the creation of less formal spaces can create spaces for PES and jobseekers, and enterprises and jobseekers, to create different dynamics for interactions. Some PES in Europe have hosted ‘speed dating’ activities for jobseeker and enterprises which is a similar approach that could be used for young people (on the crest of making the transition to employment) and enterprises. Such activities can be used to promote PES’ role in providing holistic support to labour market actors.15

Case Study 5. Kazakhstan Vocational Guidance Programme

The Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan launched a vocational guidance programme as a pilot in four regions in 2014. The programme targeted school leavers from lower and upper secondary schools and unemployed young people, and it was expanded to socially deprived young people and some other groups. In total, 33,000 young people were included in the programme. The programme was implemented by private employment agencies and non-governmental organisations. The pilot was evaluated, and it showed that the vocational guidance programme was very useful for the target groups, in terms of their future employment in line with the labour market perspectives and capabilities. The programme has since become a key component of the updated Employment Roadmap 2020 and it is offered by regional employment centres across the country.16

3.5.2 How can PES move from reactive to being proactive?

Within the context of the future of work and the evolving nature of working life PES have the potential to proactively provide workers with assistance with work-to-work transitions. This is a move from the traditional PES approach of being more reactive to being more proactive by actively reaching out to enterprises, workers and other jobseekers to promote PES services and provide guidance on professional orientation. This approach can help to maximise the potential of the labour market by maximising the skill set of each individual and on an individual level, it can help individuals to build careers that are fl exible to labour market trends.

An important element of this is being able to provide career guidance and information that is informed and reflects the latest and future of the labour market. PES can use the data they have and any insights they may have picked from working with enterprises to provide tailored guidance as well as shaping training offers that reflect growing sectors and do not train or encourage individuals to move into sectors that are declining.

PES can conduct annual surveys with enterprises about their future recruitment plans and what skills they will need in the short, medium and long-term. This information can help PES to develop their training offer, assist vacancy matching and provide better career guidance to workers and jobseekers.

In some countries across Europe and across the region, PES are starting to work with workers who are at risk of unemployment. In such instances, PES work closely with the enterprises when they are notified of job losses and PES representatives can visit employees within the workplace to provide them with advice and support to help them make the next step in their career. It can be an important first step in assisting workers to upskill or reskill so that they are better equipped for a role for a different enterprise, or in a different sector. This may reduce the likelihood of these workers becoming unemployed. However, there is little research to show that this type of career counselling is enough on its own.17

It is worth noting that working closely with enterprises and other relevant organisations (such as NGOs and entrepreneurial organisations) to provide career counselling and support to those in work can lead to fruitful collaborations with partners as this can change perceptions of PES. This is further explored in Section 7 Strategic partnerhips for employment.

3.5.3 What role do PES have in preparing jobseekers for work?

PES’ services for jobseekers should also encompass providing information to jobseekers so that they are fully prepared for the workplace and all that this entails. This can include:

- Workers’ rights and labour contracts

- Working conditions

- Expected behaviours

Jobseekers should be fully informed of their rights and the key elements of a fair labour contract so that they do not enter unfair employment. In addition, it is important for jobseekers to know what constitutes appropriate and inappropriate working conditions and what they should do if they think the working conditions are inappropriate.

It is also important that PES provide information on expected behaviours in the workplace. This would cover the expected behaviour of the jobseeker but also of their fellow workers and enterprises, and what they can do if they think the behaviour is inappropriate. This can cover gender discrimination. The ILO Centenary Declaration highlights that gender quality at work should be achieved in which work ‘ensures equal opportunities, equal participation and equal treatment’ in work, the value of work and in renumeration.18

Case Study 6. Addressing gender bias via services for jobseekers in Austria

The Austrian PES delivered the ‘FiT – Women in crafts and technology’ project, between 2006 and 2014, to address the low number of women in crafts and technology. The objective was to support stronger female participation in initial training and provide support for women to enter ‘male’ professions such as dental technicians, carpenters, car mechanics, IT technicians and others. From 2006 to 2010, 24,986 women participated in the programme. 36% of the women were under 25 years, 55% between 25 and 45 years, and 9% over 45 years. Over half of the participants who successfully completed training in the framework of FiT found a job in the field of technology and trades.19

3.6 How can PES support the transition from informal to formal employment?

PES have an important role in support the transition from employment in the informal to economy. The informal economy is referred to as all economic activities by workers not covered, or insufficiently covered, by formal arrangements and this does not cover illicit activities (as per international treaties, or national laws). PES have the potential of providing an important channel of labour market information and help ensure transparency and access in the labour market.20 This includes:

- Offering support servicers to informal workers and employers on basic legal and human rights;

- Provide information on labour market conditions, including trends on the demands and supply in the labour market;

- Open up opportunities for entry into formal jobs;

- Deliver tailored services to vulnerable groups, whom are often highly represented in the informal economy, e.g. around job search assistance and opportunities to develop skills needed by the labour market.

The ILO Recommendation 20421 concerning the transition from the informal to the formal economy calls on national governments to put in place guidance to help facilitate the transition of workers from the informal to formal economy so that all workers have opportunities for income security, guaranteed livelihoods and possibilities for entrepreneurship. In terms of employment policies, the Recommendation calls for:

- Labour market policies and institutions to be in place to help low-income households to escape poverty and access public employment programmes;

- Employment services to be delivered to those in the informal economy; and

- Activation measures to facilitate school to work transitions of young people, including youth guarantee schemes to provide access to training and employment.

Case Study 7. ‘Start and Improve Your Business (SIYB) Programme’ in Azerbaijan22

The PES in Azerbaijan has implemented a subsidy programme targeting young entrepreneurs as a way to address the high number of young people and entrepreneurs in the informal economy. The SIYB programme focuses on staring and improving small businesses as a strategy for creating more and better employment in developing economies and economies in transition. It provides training and support to those who have viable business ideas, including training on how to develop business plans. Each participant receives follow-up support via visits from the PES staff and ad hoc assistance and advice. This has encouraged businesses to grow, develop and sustain themselves.

Box 7. The ILO Centenary Declaration and Skills Development23

The ILO Centenary Declaration calls for an investment in people’s capabilities and a human centred approach.24 This puts workers’ rights and the needs, aspirations and rights of all individuals at the heart of economic, social and environmental policies. It also calls for the promotion of the acquisition of skills, competencies and qualifications for all workers throughout working lives.

This is seen as a joint responsibility of governments and social partners in order to:

- Address existing and anticipated skills gaps;

- Pay particular attention to ensuring that education and training systems are responsive to labour market needs, taking into account the evolution of work;

- Enhance workers’ capacity to make use of the opportunities available for decent work; and

- Facilitate the transition from education and training to work, with an emphasis on the effective integration of young people into the world of work.

To fulfil the aims of the Centenary Declaration, PES may want to consider working with the following types of organisations:

- Schools and other education providers;

- Training providers;

- Specialist providers (for work preparation activities);

- Private employment agencies;

- Career guidance organisations (where applicable);

- Non-governmental organisations (NGOs);

- Youth organisations.

Box 8. Supporting jobseekers to fulfil their potential:

Below is a checklist of the key features that should be delivered in high quality services for jobseekers:

- A well-functioning and up-to-date online vacancy database;

- A team of well-trained and knowledgeable frontline counsellors;

- During the initial assessment, jobseekers undergo profiling using clear guidelines and consistent approaches;

- Individual action plans are developed and agreed between the jobseeker and frontline counsellor;

- A flexible package of job search assistance support that caters for self-sufficient jobseekers and those who need help with interview techniques, building a CV and looking for jobs;

- Pre-employment training and support that provides jobseekers with an opportunity to develop employment-related skills;

- Second chance programmes that provides jobseekers with no qualifications an opportunity to develop skills and gain qualifications, using non-traditional routes;

- Career guidance information and guidance that is available to all, not only registered unemployed people. This can include information on websites, resources within PES and trained PES staff;

- A well-developed IT system that frontline counsellors can use to record information about jobseekers, assist with profiling and track the progress of each jobseeker;

- Post-employment support is available, where needed, to sustain labour market integration.

Box 9. Questions for self-reflection

Use the questions below to think about the steps your PES need to take to develop high-quality services for jobseekers and how your PES can support people to fulfil their potential.

- What IT systems do you have in place to assist with profiling of jobseekers? What changes can you make?

- What steps would you need to take to develop and implement individual action plans?

- What training do you currently offer frontline counsellors? What training will they need in the future and how can you deliver this?

- What partners do you currently work with to deliver services to jobseekers? Who could you start to work with in your region/country and why?

- ^ Please consult the European Network of Public Employment Services for specific reports, toolkits and papers on this topic: (https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1163&intPageId=3451&langId=en)

- ^ European Commission (2011) ‘Profiling sys tems for effective labour market integration’, (https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=14080&langId=en)

- ^ ILO (2017) ‘Profiling youth labour market disadvantage: A review of approaches in Europe’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_613361.pdf)

- ^ ILO and European Commission (2015) ‘The role of employment service provides: Guide to anticipating and matching skills and jobs’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_445932.pdf)

- ^ ILO and European Commission (2015) ‘The role of employment service provides: Guide to anticipating and matching skills and jobs’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_445932.pdf)

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ European Commission (2012) ‘Activation and integration: working with individual action plans: Toolkit for Public Employment Services’ (https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=14081&langId=en)

- ^ ILO (2018) ‘Does work-based learning facilitate transitions to decent work?’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_635797.pdf)

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ ILO (2017) ‘Towards policies tackling the current youth employment challenges in Eastern Europe and Central Asia’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_590104.pdf)

- ^ European Commission (2016) ‘PES Tutors in upper secondary schools pilot project, European PES Network PES Practice’ (https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=15226&langId=en)

- ^ For further information please see: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1079

- ^ ILO (2019) ‘Work for a brighter future – Global Commission on the Future of Work’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/--dgreports/---cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_662410.pdf)

- ^ European Commission (2017) ‘PES Network Seminar: Career Guidance and Lifelong Learning’ (https://ec.europa.eu/social/ BlobServlet?docId=18459&langId=en)

- ^ European Commission (2017) ‘PES Network Seminar: Career Guidance and Lifelong Learning’ (https://ec.europa.eu/social/ BlobServlet?docId=18459&langId=en)

- ^ ILO (2017) ‘Towards policies tackling the current youth employment challenges in Eastern Europe and Central Asia’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_590104.pdf)

- ^ European Commission (2019) ‘How do PES act to prevent unemployment in a changing world of work?’ (https://ec.europa.eu/ social/BlobServlet?docId=20600&langId=en)

- ^ ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work (2019) (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_711674.pdf)

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=15231&langId=en

- ^ ILO (2013) ‘The informal economy and decent work: a policy resource guide, supporting transitions to formality’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---europe/---ro-geneva/---sro-moscow/documents/publication/wcms_345060.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2015) ‘Recommendation 2014 concerning the transition form the informal to the formal economy’ (https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_377774.pdf)

- ^ ILO (2015) ‘Get formal, be successful: Supporting the transition to formality of youth-led enterprises in Azerbaijan’ (https://www.ilo.org/moscow/news/WCMS_373481/lang--en/index.htm)

- ^ https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/mission-and-objectives/centenary-declaration/lang--en/index.htm

- ^ Comyn, P. ‘Skills and lifelong learning to facilitate access to and transitions in the labour market’