- Contents

- 1. Introduction and background

- Structure of the report

- Uses of statistics on work relationships

- Overview of the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93)

- Impact of the 19th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization

- Issues addressed in the revision of ICSE-93

- Outline of the proposed new standards

- Main differences between the proposed new standards and ICSE-93

- Guidelines for data collection and measurement approach

1. Introduction and background

1. International standards for labour statistics serve two main purposes: to provide up-to-date guidelines for the development of national official statistics on a particular topic; and to promote international comparability of the resulting statistics. Periodic revision and update of these standards are needed to ensure that they adequately reflect new developments in labour markets in countries at different stages of development, and that they incorporate identified best practices and advances in statistical methodology so as best to meet emerging policy concerns.

2. The current international standard for statistics on work relationships is the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93), adopted in 1993 as a resolution of the 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). It provides five substantive categories and defines the widely used distinction between self-employment and paid employment. Its revision was mandated in 2013 at the 19th ICLS in order to address a wide range of concerns.

3. A central concern is that the five substantive categories defined in ICSE-93 do not provide sufficient information to adequately monitor the changes in employment arrangements that are taking place in many countries and are not sufficiently detailed to monitor various forms of non-standard employment. A variety of new, or non-standard, arrangements that aim to increase flexibility in the labour market are also generating a need for statistical information to monitor the impact of these arrangements on workers and the functioning of the labour market. Some of these arrangements change the balance of economic risk between workers and enterprises and are leading to uncertainty about the boundary between self-employment and paid employment.

4. An important focus of work to revise ICSE-93 was therefore to develop proposals that will support the provision of more comprehensive and internationally comparable statistics on the growth of non-standard forms of employment. Non-standard employment may in some cases be voluntary and have positive outcomes for both workers and employers. In other cases, however, it is associated with job and income insecurity. It may also “pose challenges for enterprises, the overall performance of labour markets and economies as well as societies at large”.1

5. Non-standard employment refers to employment arrangements that deviate from the “standard employment relationship”, understood as work that is full time, indefinite, formal, and part of a subordinate relationship between an employee and employer. Nonstandard employment arrangements include:

- emporary employment, such as through fixed-term contracts, casual or daily work and some forms of on-call work;

- part-time and on-call work;

- multi-party employment arrangements such as labour hire, dispatch, and brokerage, temporary agency work and subcontracted labour supply; and

- “Dependent self-employment” when dependent workers have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature.

6. While part-time work is considered to be a form of non-standard employment, the provision of statistics on part-time and on-call work are covered to a large extent through existing standards for the measurement of working time and working time arrangements adopted by the 18th ICLS in 2008. There are no current standards for statistics on the other types of non-standard employment. The 15th ICLS resolution does provide advice on “the possible statistical treatment of particular groups” including those related to temporary employment, casual work and dependent self-employment. This advice is not formally part of the classification of ICSE-93, however.

7. To assist in the development of proposals to replace ICSE-93, the ILO established a working group comprising producers and users of labour and economic statistics from national government agencies in all regions, intergovernmental agencies, and workers’ and employers’ organizations. This group met four times from May 2015 to September 2017. To widen the consultation process and obtain feedback on the proposals developed by the working group, the ILO also conducted a series of preparatory Regional Meetings of labour statisticians, in all regions of the world from late 2016 and throughout 2017. These meetings focused on both relevance to the regional context and technical feasibility of the proposed new standards. Opportunities for testing of the proposals were identified in several countries and testing is ongoing.

8. The outcome of this development and consultation process is a series of proposals to replace ICSE-93 with a suite of statistical standards and classifications. A central element is a revised International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-18). It includes ten categories to allow better identification of workers with non-standard employment arrangements including those with fixed-term and with casual and short-term contracts of employment, to address concerns about both the blurring of the boundary between paid employment and self-employment and to measure the growth of dependent selfemployment.

9. The need for better statistics on various dimensions of non-standard employment is also provided through a series of cross-cutting variables and categories, which provide more detailed information on the degree of stability and permanence of the work. They cover topics such as duration of contract, multi-party employment arrangements, and job dependent social protection. A new International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW18) extends ICSE-18 to cover all forms of work. The proposals are integrated by a conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships which defines the key concepts, variables and classification schemes included in the new standards.

10. These standards are proposed in the form of a draft resolution concerning statistics on work relationships, provided in the appendix to this report, to be reviewed and amended as necessary and considered for adoption by the 20th ICLS.

Structure of the report

11. The report consists of six chapters. This first chapter presents background information on the revision work and the demand for statistics on employment relationships, an outline of the proposed new standards and approach to data collection and an overview of the current relevant standards. The remaining chapters are intended to serve as a guide to the draft resolution. Chapter 2 describes the conceptual framework and model that underpin the proposed classifications and statistical variables included in the new standards. Chapter 3 discusses the proposal for a revised International Classification of Status in Employment, while Chapter 4 covers the proposal for a new ICSaW-18. Chapter 5 is concerned with the proposed cross-cutting variables. Chapter 6 concludes the report by briefly discussing the sections of the resolution dealing with data sources and future work.

12. The report and draft resolution have been adapted from a more detailed paper on the conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships, which was developed and progressively updated in consultation with the working group. An updated version of the conceptual framework paper, as well as guidelines for data collection, will be provided as room documents during the 20th ICLS.

Uses of statistics on work relationships

13. Statistics on the relationship between the worker and the economic unit in which, or for which, the person works, including statistics in which jobs are currently classified by status in employment, are needed for a wide variety of purposes in both economic and social analysis. They provide information on the nature of the economic risk and authority that individuals experience at work, and on the strength and nature of the attachment of workers to the economic unit in which they work. In statistics on employment they provide an indicator of the prevalence of unstable or insecure employment situations.

14. Changes in status in employment distributions may reflect the impact of economic cycles on employment in higher risk, lower income, less secure jobs. For example, an increase in self-employment as a percentage of total employment may occur when workers who lose jobs in paid employment engage in various forms of self-employment.

15. Economic and labour market policy analysts use statistics on status in employment to assess the impact of self-employment and entrepreneurialism on employment and economic growth and to evaluate government policies and proposals related to economic development and job creation.

16. Statistics classified by status in employment are important for the identification of wage employment and its distribution and for the production and analysis of statistics on wages, earnings and labour costs. In some countries they are needed to estimate revenue from social contributions and assist in determining the level of contributions to be paid.

17. In social statistics, status in employment is an important explanatory variable in its own right and is used as an input variable in the production of statistics on informal employment and on the socio-economic status of persons and households.

18. Data classified by status in employment also provide an important input to national accounts. The income derived from employment of employees is treated in the System of National Accounts (SNA) as compensation of employees, whereas the remuneration of the self-employed is treated as mixed income.

19. Statistics on work relationships are needed to provide information on the extent of authority, dependence and economic risk experienced by various groups of policy concern in own-use production of goods and services, in volunteer work and in unpaid trainee work, as well as in employment. These groups include but are not limited to women and men, young people, children, migrants and ethnic minorities. They can provide important information to support the assessment of the economic and social conditions of these various groups.

20. Reflecting these diverse uses, statistics on employed persons or jobs by status in employment, and on other variables related to the stability and permanence of work relationships, are widely collected in household-based collections such as Labour Force Surveys, social surveys and population censuses as well as in employer surveys. They may also be compiled from administrative records if these have been adapted for statistical purposes. Statistics on work relationships in other forms of work may also be compiled from such sources, or from special purpose data collections, depending on relevance and priorities in the national context.

21. The development and use of a consistent and coherent system of statistical standards for work relationships, including on status in employment, will therefore facilitate more meaningful comparisons of data from different sources (for example, household surveys with employer surveys or administrative sources where coverage may be limited to employees). The adoption, in addition to the classification of status in employment, of a classification of status of worker covering all forms of work, as well as a comprehensive set of standard variables and categories covering various aspects of the stability of work arrangements, should provide more relevant, detailed, harmonized and coherent statistics with the aim of better satisfying this wide range of analytical and policy needs.

Overview of the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93)

22. ICSE-93 classifies jobs with respect to the type of explicit or implicit contract of employment between the job holder and the economic unit in which he or she is employed. The following five substantive categories are specified in addition to a sixth category: “Workers not classifiable by status”:

- Employees.

- Employers.

- Own-account workers.

- Members of producers’ cooperatives.

- Contributing family workers

23. While the self-employed are not defined as a substantive group in ICSE-93, the groups are defined with reference to the distinction between “paid employment jobs” and “selfemployment jobs”. The last four groups listed above form the self-employed. The structure of ICSE-93 can thus be represented as follows:

- Paid employment jobs:

- Self-employment jobs:

- Employers.

- Own-account workers.

- Contributing family workers.

- Members of producers’ cooperatives.

- Workers not classifiable by status.

24. The final group, “Workers not classifiable by status”, includes “those for whom insufficient relevant information is available and/or who cannot be included in any of the preceding categories”. Since this group does not relate to any observable phenomenon, it is proposed to delete this category from the new standards and to replace it with guidelines on the treatment of missing or insufficient data.

25. The ICSE-93 also provides advice on “the possible statistical treatment of particular groups” that are relevant for analysis of the changes that are taking place in the labour market and could potentially satisfy some of the unmet needs for statistics. Some of the groups represent subcategories of one of the specific ICSE-93 categories. Others may cut across two or more of these categories. It suggests that according to national requirements, countries may need and be able to distinguish one or more of the groups and may also create other groups. The advice provided covers the following groups:

- (a) owner-managers of incorporated enterprises;

- (b) regular employees with fixed-term contracts;

- (c) regular employees with contracts without limits of time;

- (d) workers in precarious employment;

- (e) casual workers;

- (f) workers in short-term employment;

- (g) workers in seasonal employment;

- (h) outworkers;

- (i) contractors;

- (j) workers who hold explicit or implicit contracts of “paid employment” from one organization, but who work at the site of and/or under instructions from a second organization which pays the first organization a fee for their services;

- (k) work gang (crew) members;

- (l) employment promotion employees;

- (m) apprentices or trainees;

- (n ) employers of regular employees;

- (o) core own-account workers;

- (p) franchisees;

- (q) sharecroppers;

- (r) communal resource exploiters;

- (s) subsistence workers.

26. These groups are not organized into a coherent classificatory framework, however, and the advice provided in ICSE-93 resolution is not definitive about the treatment of some of the groups. For example, owner-managers of incorporated enterprises and contractors may be classified as employees or as self-employed workers according to national circumstances. As a result, international comparison and analysis of trends related to the mix between paid employment and various categories of self-employment are compromised, since national practices are not consistent.

27. Based on the discussions at the 19th ICLS, among members of the working group and during the regional consultations, the definitions and statistical treatment of several of these groups were identified as major issues that needed to be addressed in the review of ICSE-93. In many cases these particular groups reflected various types of employment arrangements that national statistical agencies found difficult to fit into any of the five substantive categories.

Impact of the 19th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization

28. The 19th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization (19th ICLS resolution I) adopted in 2013, updated the previous international standards relating to statistics of the economically active population, employment, unemployment and underemployment (13th ICLS, 1982) and related guidelines. It introduced the first international statistical definition of work and a number of features that are particularly relevant for the revision of ICSE-93, including:

- (a) a more refined concept and definition of employment that focuses on work for pay or profit to serve as the basis for the production of labour force statistics;

- (b) a comprehensive framework for work statistics that distinguishes between employment and other forms of work, including own-use production work, volunteer work, and unpaid trainee work;

- (c) operational definitions and guidelines to enable comprehensive measurement of participation and time spent in forms of work other than employment, particularly production of goods for own final use, provision of services for own final use, and volunteer work.

29. The 19th ICLS resolution notes that the standards should serve to facilitate the production of different subsets of work statistics for different purposes as part of an integrated national system that is based on common concepts and definitions. This objective is equally relevant for the new standards that will replace ICSE-93.

30. The specific elements of the 19th ICLS standards that are most relevant to the revision of ICSE-93 are the reference concepts for work statistics, including the definition of work itself, and the definitions of each form of work.

The concept of work

31. According to the 19th ICLS, work comprises any activity performed by persons of any sex and age to produce goods or to provide services for use by others or for own use. It excludes activities that do not involve the production of goods or services (for example, begging and stealing), self-care (for example, personal grooming and hygiene) and activities that cannot be performed by another person on one’s own behalf (for example, sleeping, learning and activities for own recreation).

Forms of work

32. Five mutually exclusive forms of work are identified for separate measurement. These forms of work are distinguished on the basis of the intended destination of the production (for own final use; or for use by others, i.e. other economic units) and the nature of the transaction (i.e. monetary or non-monetary transactions and transfers), as follows:

- (a) own-use production work comprising production of goods and services for own final use;

- (b) employment work comprising work performed for others in exchange for pay or profit;

- (c) unpaid trainee work comprising work performed for others without pay to acquire workplace experience or skills;

- (d) volunteer work comprising non-compulsory work performed for others without pay;

- (e) other work activities.2

Alignment of the framework for work statistics with the System of National Accounts (SNA)

33. The concept of work and the forms of work were aligned with the SNA so as to ensure that all activities within the SNA production boundary could be separately identified and captured in statistics compiled according to the new standards. The 19th ICLS resolution I notes that:

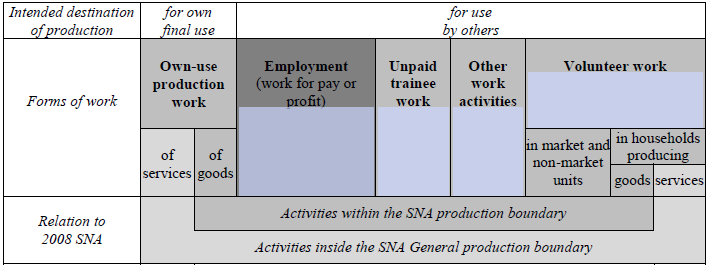

The relationship between the forms of work and the production boundaries defined in the SNA is shown in figure 1. All the activities within the SNA production boundary were counted as employment according to the old standards for labour statistics and were therefore within the scope of ICSE-93.

Figure 1. Forms of work and the System of National Accounts 2008

Issues addressed in the revision of ICSE-93

35. Based on the discussions at the 19th ICLS and among members of the working group, the following key issues were identified as the most important to be addressed in revising ICSE-93:

- (a) the extension of the new statistical standards to cover all forms of work specified in the 19th ICLS resolution I and to reflect the narrower definition of employment defined in that standard;

- (b) the need for an overarching conceptual framework to ensure coherence between the various classifications and variables specified in the new standards and between the various domains of social, labour and economic statistics, and to facilitate the provision of harmonized statistics from different sources and domains;

- (c) the relevance and usefulness of maintaining a distinction between paid employment and self-employment as a dichotomous pair of aggregate categories, given the wide range of analytical uses of these categories and the increasing number of types of employment arrangement that do not fit comfortably into either category;

- (d) the boundary between self-employment and paid employment, particularly with respect to working proprietors of incorporated enterprises and dependent workers who have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature;

- (e) applicability of the standards to informal employment situations, especially informal employees;

- (f) the identification of workers in various non-standard forms of employment such as casual, short-term, temporary and seasonal employees, and workers on zero-hours contracts;

- (g) the need for guidelines on data collection, questionnaire design, derivation and adaptation of the standards for national use;

- (h) the identification and statistical treatment of various specific types of worker including:

- apprentices, trainees and interns;

- entrepreneurs;

- wage and salary earners;

- family workers;

- domestic workers;

- homeworkers and outworkers;

- members of producers’ cooperatives;

- workers with multi-party employment arrangements, including those engaged

- by labour hire agencies or temporary employment agencies.

36. It would be difficult, within a single classificatory framework, to provide a set of mutually exclusive categories that would allow the identification of all of these groups and satisfy the numerous and very different purposes for which statistics on the employment relationship are required. It was agreed therefore to develop a set of proposals to replace ICSE-93 with a suite of standards for statistics on the relationships between workers and the economic unit for which they work, rather than incorporating a number of overlapping concepts and characteristics in a single complex classification.

Outline of the proposed new standards

37. The draft resolution concerning statistics on work relationships aims to promote the coherence and integration of statistics from different sources on multiple characteristics of work relationships, by providing:

- (a) an overarching conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships which defines the key concepts, variables and classification schemes included in the new standards for statistics on work relationships;

- (b) a revised International Classification of Status in Employment (to be designated ICSE-18);

- (c) an International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW-18) as a reference classification covering all forms of work;

- (d) a set of cross-cutting variables and categories that support the derivation and analysis of the status at work categories;

- (e) operational concepts, definitions and guidelines for the collection and compilation of statistics on status in employment and the cross-cutting variables.

38. The revised ICSE-18 comprises ten categories which may be aggregated according to two alternative classification structures. The first structure, based on the type of authority that the worker exercises over the economic unit for which he/she works, provides categories at its top level for “dependent” and “independent workers”. The second structure, based on the type of economic risk to which the worker is exposed, creates a dichotomy between “workers in employment for pay” and “workers in employment for profit”. This is similar to the traditional distinction between paid employment and self-employment.

39. The ICSE-93 categories of employers, own-account workers, contributing family workers and employees have been retained in the proposed ICSE-18. The aggregate categories in the ICSE-18 structure based on the type of authority are therefore quite similar to the ICSE93 categories. In addition, the revised ICSE includes four subcategories of employees, separate categories for owner-operators of corporations and a separate category for dependent contractors.

40. A separate category for workers in producers’ cooperatives has not been retained in ICSE18, as the number of persons reported as employed in this ICSE-93 category is very small in almost all countries. Many countries do not use this category in their national statistics.4

41. The proposed new category of “dependent contractors” refers to “workers who have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature to provide goods or services for or on behalf of another economic unit, are not employees of that economic unit, but are dependent on that unit for organization and execution of the work or for access to the market.”. They may either provide labour to others while having contractual arrangements similar to self-employment or else they own and operate a business without employees but do not have full control or authority over their work. This new category is needed to provide information on the group of workers frequently referred to as the “dependent selfemployed”, which was one of the most important objectives of the revision work.

42. The proposed ICSaW-18 is an extension of the classification of Status in Employment to cover all forms of work, including own-use production work, volunteer work and unpaid trainee work, as well as employment. Its purpose is to allow the production of conceptually consistent statistics on different populations and from different sources, rather than to be used in its entirety for the compilation of statistics from any particular survey. The categories in ICSaW are defined in such a way as to allow the provision of separate statistics on activities within and beyond the SNA production boundary.

43. The classifications according to status are complemented by a set of cross-cutting variables and categories which provide definitions and categories for types of arrangement that cut across several status categories. Many of these variables are regularly included in most Labour Force Surveys but are not covered by internationally agreed statistical standards. The proposals therefore seek not only to provide more relevant and detailed statistics on status in employment but also to promote greater harmonization, coherence and international comparability of statistics on various aspects of the contractual and other conditions in which work is performed.

Main differences between the proposed new standards and ICSE-93

44. The proposed new standards have a wider scope than ICSE-93, since the overall framework can be applied to all forms of work defined in the 19th ICLS resolution I, whereas ICSE-93 is restricted to employment as defined by the 13th ICLS. Some of the proposed new classifications and variables apply to all forms of work whereas others are restricted to a single form or to certain forms of work.

45. While the proposed ICSaW includes categories relevant to all forms of work, the proposed ICSE-18 is applicable to employment as defined by the 19th ICLS. It is therefore narrower in scope than ICSE-93.

46. The ICSE-18 is generally more detailed than ICSE-93 and includes ten categories at its most detailed level, compared to the five in ICSE-93. Some of the concepts defined in ICSE-93 as “particular groups” for optional use at national level are covered by new categories in ICSE-18, including owner-operators of corporations, dependent contractors and subcategories of employee. Since members of producers’ cooperatives are no longer identified as a separate category in the revised ICSE, the owner-operators of enterprises that are members of producers’ cooperatives will generally be classified either as employers, or as independent workers without employees, as appropriate. The “crosscutting” variables and classification schemes proposed in the new standards were not included in ICSE-93 but do reflect some of the ICSE-93 “particular groups”, or the statistical needs underlying them. More detailed information about the differences between ICSE-93 and ICSE-18 is provided in Chapter 3.

Guidelines for data collection and measurement approach

47. A major criticism of ICSE-93 is the absence of guidance on methods and approaches to collect data on status in employment and on work relationships more generally. Reflecting this concern and to ensure the statistical feasibility of the proposals, data collection guidelines have been developed and tested (to the extent possible) in parallel with the conceptual development work. They will provide guidance on the collection of statistics on work relationships in Labour Force Surveys, as well as on the use of reduced sets of questions in statistical collections where the fully detailed categories are not collected. Such data collections could include household surveys, the population census, employer surveys and administrative collections.

48. The approach proposed for the collection of statistics on status in employment in household surveys builds on existing common practice by asking an initial question to allow respondents to self-identify based on the categories “self-employed”, “employee”, “family worker” and “trainee”. Depending on the response to the initial question, respondents are directed to different streams of questions to allow the identification of dependent contractors, classification to more detailed levels of status in employment and to verify the accuracy of the initial response. While this approach may increase respondent burden and the complexity of questionnaires, the importance of collecting information on status in employment with an adequate degree of precision is widely acknowledged. Reliance on self-identification alone is likely to result in significant levels of misclassification.5 Much of the information required is already commonly collected in Labour Force Surveys.

- ^ ILO 2016.

- ^ “Other work activities” include such activities as unpaid community service and unpaid work by prisoners, when ordered by a court or similar authority, and unpaid military or alternative civilian service, which may be treated as a distinct form of work for measurement (such as compulsory work performed without pay others).

- ^ ILO 2013c.

- ^ The reasons for not retaining a separate category for members of producers’ cooperatives are discussed in more depth in Chapter 3.

- ^ Abraham, K. et al. 2017, Bonin, H. and Rinne, U., 2017.

- 1. Introduction and background