- 1. Introduction and background

- Structure of the report

- Uses of statistics on work relationships

- Overview of the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93)

- Impact of the 19th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization

- Issues addressed in the revision of ICSE-93

- Outline of the proposed new standards

- Main differences between the proposed new standards and ICSE-93

- Guidelines for data collection and measurement approach

- 2. Conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships

- 3. Status in employment

- 4. International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW-18)

- 5. Cross-cutting variables and categories

- 6. Data sources, indicators and future work

- References

- Appendix

- Preamble

- Objectives and scope

- Reference concepts

- The International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-18)

- Definitions and explanatory notes for categories in the two hierarchies of the International Classification of Status in Employment

- International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW-18)

- Definitions of the categories in ICSaW-18 that are not included in ICSE-18

- Cross-cutting variables and categories

- Duration of the job or work activity

- Working time

- Reasons for non-permanent employment

- Type of employment agreement

- Form of remuneration

- Seasonal workers

- Type of workplace

- Domestic workers

- Home-based workers

- Multi-party work relationships

- Variables related to the measurement of informal employment relationships

- Data sources and guidelines for data collection

- Indicators

- Future work

1. Introduction and background

1. International standards for labour statistics serve two main purposes: to provide up-to-date guidelines for the development of national official statistics on a particular topic; and to promote international comparability of the resulting statistics. Periodic revision and update of these standards are needed to ensure that they adequately reflect new developments in labour markets in countries at different stages of development, and that they incorporate identified best practices and advances in statistical methodology so as best to meet emerging policy concerns.

2. The current international standard for statistics on work relationships is the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93), adopted in 1993 as a resolution of the 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). It provides five substantive categories and defines the widely used distinction between self-employment and paid employment. Its revision was mandated in 2013 at the 19th ICLS in order to address a wide range of concerns.

3. A central concern is that the five substantive categories defined in ICSE-93 do not provide sufficient information to adequately monitor the changes in employment arrangements that are taking place in many countries and are not sufficiently detailed to monitor various forms of non-standard employment. A variety of new, or non-standard, arrangements that aim to increase flexibility in the labour market are also generating a need for statistical information to monitor the impact of these arrangements on workers and the functioning of the labour market. Some of these arrangements change the balance of economic risk between workers and enterprises and are leading to uncertainty about the boundary between self-employment and paid employment.

4. An important focus of work to revise ICSE-93 was therefore to develop proposals that will support the provision of more comprehensive and internationally comparable statistics on the growth of non-standard forms of employment. Non-standard employment may in some cases be voluntary and have positive outcomes for both workers and employers. In other cases, however, it is associated with job and income insecurity. It may also “pose challenges for enterprises, the overall performance of labour markets and economies as well as societies at large”.1

5. Non-standard employment refers to employment arrangements that deviate from the “standard employment relationship”, understood as work that is full time, indefinite, formal, and part of a subordinate relationship between an employee and employer. Nonstandard employment arrangements include:

- emporary employment, such as through fixed-term contracts, casual or daily work and some forms of on-call work;

- part-time and on-call work;

- multi-party employment arrangements such as labour hire, dispatch, and brokerage, temporary agency work and subcontracted labour supply; and

- “Dependent self-employment” when dependent workers have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature.

6. While part-time work is considered to be a form of non-standard employment, the provision of statistics on part-time and on-call work are covered to a large extent through existing standards for the measurement of working time and working time arrangements adopted by the 18th ICLS in 2008. There are no current standards for statistics on the other types of non-standard employment. The 15th ICLS resolution does provide advice on “the possible statistical treatment of particular groups” including those related to temporary employment, casual work and dependent self-employment. This advice is not formally part of the classification of ICSE-93, however.

7. To assist in the development of proposals to replace ICSE-93, the ILO established a working group comprising producers and users of labour and economic statistics from national government agencies in all regions, intergovernmental agencies, and workers’ and employers’ organizations. This group met four times from May 2015 to September 2017. To widen the consultation process and obtain feedback on the proposals developed by the working group, the ILO also conducted a series of preparatory Regional Meetings of labour statisticians, in all regions of the world from late 2016 and throughout 2017. These meetings focused on both relevance to the regional context and technical feasibility of the proposed new standards. Opportunities for testing of the proposals were identified in several countries and testing is ongoing.

8. The outcome of this development and consultation process is a series of proposals to replace ICSE-93 with a suite of statistical standards and classifications. A central element is a revised International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-18). It includes ten categories to allow better identification of workers with non-standard employment arrangements including those with fixed-term and with casual and short-term contracts of employment, to address concerns about both the blurring of the boundary between paid employment and self-employment and to measure the growth of dependent selfemployment.

9. The need for better statistics on various dimensions of non-standard employment is also provided through a series of cross-cutting variables and categories, which provide more detailed information on the degree of stability and permanence of the work. They cover topics such as duration of contract, multi-party employment arrangements, and job dependent social protection. A new International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW18) extends ICSE-18 to cover all forms of work. The proposals are integrated by a conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships which defines the key concepts, variables and classification schemes included in the new standards.

10. These standards are proposed in the form of a draft resolution concerning statistics on work relationships, provided in the appendix to this report, to be reviewed and amended as necessary and considered for adoption by the 20th ICLS.

Structure of the report

11. The report consists of six chapters. This first chapter presents background information on the revision work and the demand for statistics on employment relationships, an outline of the proposed new standards and approach to data collection and an overview of the current relevant standards. The remaining chapters are intended to serve as a guide to the draft resolution. Chapter 2 describes the conceptual framework and model that underpin the proposed classifications and statistical variables included in the new standards. Chapter 3 discusses the proposal for a revised International Classification of Status in Employment, while Chapter 4 covers the proposal for a new ICSaW-18. Chapter 5 is concerned with the proposed cross-cutting variables. Chapter 6 concludes the report by briefly discussing the sections of the resolution dealing with data sources and future work.

12. The report and draft resolution have been adapted from a more detailed paper on the conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships, which was developed and progressively updated in consultation with the working group. An updated version of the conceptual framework paper, as well as guidelines for data collection, will be provided as room documents during the 20th ICLS.

Uses of statistics on work relationships

13. Statistics on the relationship between the worker and the economic unit in which, or for which, the person works, including statistics in which jobs are currently classified by status in employment, are needed for a wide variety of purposes in both economic and social analysis. They provide information on the nature of the economic risk and authority that individuals experience at work, and on the strength and nature of the attachment of workers to the economic unit in which they work. In statistics on employment they provide an indicator of the prevalence of unstable or insecure employment situations.

14. Changes in status in employment distributions may reflect the impact of economic cycles on employment in higher risk, lower income, less secure jobs. For example, an increase in self-employment as a percentage of total employment may occur when workers who lose jobs in paid employment engage in various forms of self-employment.

15. Economic and labour market policy analysts use statistics on status in employment to assess the impact of self-employment and entrepreneurialism on employment and economic growth and to evaluate government policies and proposals related to economic development and job creation.

16. Statistics classified by status in employment are important for the identification of wage employment and its distribution and for the production and analysis of statistics on wages, earnings and labour costs. In some countries they are needed to estimate revenue from social contributions and assist in determining the level of contributions to be paid.

17. In social statistics, status in employment is an important explanatory variable in its own right and is used as an input variable in the production of statistics on informal employment and on the socio-economic status of persons and households.

18. Data classified by status in employment also provide an important input to national accounts. The income derived from employment of employees is treated in the System of National Accounts (SNA) as compensation of employees, whereas the remuneration of the self-employed is treated as mixed income.

19. Statistics on work relationships are needed to provide information on the extent of authority, dependence and economic risk experienced by various groups of policy concern in own-use production of goods and services, in volunteer work and in unpaid trainee work, as well as in employment. These groups include but are not limited to women and men, young people, children, migrants and ethnic minorities. They can provide important information to support the assessment of the economic and social conditions of these various groups.

20. Reflecting these diverse uses, statistics on employed persons or jobs by status in employment, and on other variables related to the stability and permanence of work relationships, are widely collected in household-based collections such as Labour Force Surveys, social surveys and population censuses as well as in employer surveys. They may also be compiled from administrative records if these have been adapted for statistical purposes. Statistics on work relationships in other forms of work may also be compiled from such sources, or from special purpose data collections, depending on relevance and priorities in the national context.

21. The development and use of a consistent and coherent system of statistical standards for work relationships, including on status in employment, will therefore facilitate more meaningful comparisons of data from different sources (for example, household surveys with employer surveys or administrative sources where coverage may be limited to employees). The adoption, in addition to the classification of status in employment, of a classification of status of worker covering all forms of work, as well as a comprehensive set of standard variables and categories covering various aspects of the stability of work arrangements, should provide more relevant, detailed, harmonized and coherent statistics with the aim of better satisfying this wide range of analytical and policy needs.

Overview of the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93)

22. ICSE-93 classifies jobs with respect to the type of explicit or implicit contract of employment between the job holder and the economic unit in which he or she is employed. The following five substantive categories are specified in addition to a sixth category: “Workers not classifiable by status”:

- Employees.

- Employers.

- Own-account workers.

- Members of producers’ cooperatives.

- Contributing family workers

23. While the self-employed are not defined as a substantive group in ICSE-93, the groups are defined with reference to the distinction between “paid employment jobs” and “selfemployment jobs”. The last four groups listed above form the self-employed. The structure of ICSE-93 can thus be represented as follows:

- Paid employment jobs:

- Employees.

- Self-employment jobs:

- Employers.

- Own-account workers.

- Contributing family workers.

- Members of producers’ cooperatives.

- Workers not classifiable by status.

24. The final group, “Workers not classifiable by status”, includes “those for whom insufficient relevant information is available and/or who cannot be included in any of the preceding categories”. Since this group does not relate to any observable phenomenon, it is proposed to delete this category from the new standards and to replace it with guidelines on the treatment of missing or insufficient data.

25. The ICSE-93 also provides advice on “the possible statistical treatment of particular groups” that are relevant for analysis of the changes that are taking place in the labour market and could potentially satisfy some of the unmet needs for statistics. Some of the groups represent subcategories of one of the specific ICSE-93 categories. Others may cut across two or more of these categories. It suggests that according to national requirements, countries may need and be able to distinguish one or more of the groups and may also create other groups. The advice provided covers the following groups:

- (a) owner-managers of incorporated enterprises;

- (b) regular employees with fixed-term contracts;

- (c) regular employees with contracts without limits of time;

- (d) workers in precarious employment;

- (e) casual workers;

- (f) workers in short-term employment;

- (g) workers in seasonal employment;

- (h) outworkers;

contractors;

contractors; - (j) workers who hold explicit or implicit contracts of “paid employment” from one organization, but who work at the site of and/or under instructions from a second organization which pays the first organization a fee for their services;

- (k) work gang (crew) members;

- (l) employment promotion employees;

- (m) apprentices or trainees;

employers of regular employees;

employers of regular employees; - (o) core own-account workers;

- (p) franchisees;

- (q) sharecroppers;

- (r) communal resource exploiters;

- (s) subsistence workers.

26. These groups are not organized into a coherent classificatory framework, however, and the advice provided in ICSE-93 resolution is not definitive about the treatment of some of the groups. For example, owner-managers of incorporated enterprises and contractors may be classified as employees or as self-employed workers according to national circumstances. As a result, international comparison and analysis of trends related to the mix between paid employment and various categories of self-employment are compromised, since national practices are not consistent.

27. Based on the discussions at the 19th ICLS, among members of the working group and during the regional consultations, the definitions and statistical treatment of several of these groups were identified as major issues that needed to be addressed in the review of ICSE-93. In many cases these particular groups reflected various types of employment arrangements that national statistical agencies found difficult to fit into any of the five substantive categories.

Impact of the 19th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization

28. The 19th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization (19th ICLS resolution I) adopted in 2013, updated the previous international standards relating to statistics of the economically active population, employment, unemployment and underemployment (13th ICLS, 1982) and related guidelines. It introduced the first international statistical definition of work and a number of features that are particularly relevant for the revision of ICSE-93, including:

- (a) a more refined concept and definition of employment that focuses on work for pay or profit to serve as the basis for the production of labour force statistics;

- (b) a comprehensive framework for work statistics that distinguishes between employment and other forms of work, including own-use production work, volunteer work, and unpaid trainee work;

- (c) operational definitions and guidelines to enable comprehensive measurement of participation and time spent in forms of work other than employment, particularly production of goods for own final use, provision of services for own final use, and volunteer work.

29. The 19th ICLS resolution notes that the standards should serve to facilitate the production of different subsets of work statistics for different purposes as part of an integrated national system that is based on common concepts and definitions. This objective is equally relevant for the new standards that will replace ICSE-93.

30. The specific elements of the 19th ICLS standards that are most relevant to the revision of ICSE-93 are the reference concepts for work statistics, including the definition of work itself, and the definitions of each form of work.

The concept of work

31. According to the 19th ICLS, work comprises any activity performed by persons of any sex and age to produce goods or to provide services for use by others or for own use. It excludes activities that do not involve the production of goods or services (for example, begging and stealing), self-care (for example, personal grooming and hygiene) and activities that cannot be performed by another person on one’s own behalf (for example, sleeping, learning and activities for own recreation).

Forms of work

32. Five mutually exclusive forms of work are identified for separate measurement. These forms of work are distinguished on the basis of the intended destination of the production (for own final use; or for use by others, i.e. other economic units) and the nature of the transaction (i.e. monetary or non-monetary transactions and transfers), as follows:

- (a) own-use production work comprising production of goods and services for own final use;

- (b) employment work comprising work performed for others in exchange for pay or profit;

- (c) unpaid trainee work comprising work performed for others without pay to acquire workplace experience or skills;

- (d) volunteer work comprising non-compulsory work performed for others without pay;

- (e) other work activities.2

Alignment of the framework for work statistics with the System of National Accounts (SNA)

33. The concept of work and the forms of work were aligned with the SNA so as to ensure that all activities within the SNA production boundary could be separately identified and captured in statistics compiled according to the new standards. The 19th ICLS resolution I notes that:

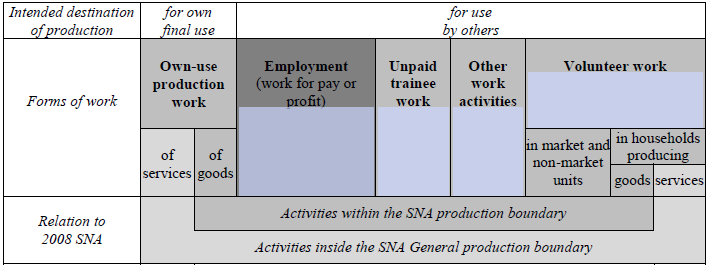

The relationship between the forms of work and the production boundaries defined in the SNA is shown in figure 1. All the activities within the SNA production boundary were counted as employment according to the old standards for labour statistics and were therefore within the scope of ICSE-93.

Figure 1. Forms of work and the System of National Accounts 2008

Issues addressed in the revision of ICSE-93

35. Based on the discussions at the 19th ICLS and among members of the working group, the following key issues were identified as the most important to be addressed in revising ICSE-93:

- (a) the extension of the new statistical standards to cover all forms of work specified in the 19th ICLS resolution I and to reflect the narrower definition of employment defined in that standard;

- (b) the need for an overarching conceptual framework to ensure coherence between the various classifications and variables specified in the new standards and between the various domains of social, labour and economic statistics, and to facilitate the provision of harmonized statistics from different sources and domains;

- (c) the relevance and usefulness of maintaining a distinction between paid employment and self-employment as a dichotomous pair of aggregate categories, given the wide range of analytical uses of these categories and the increasing number of types of employment arrangement that do not fit comfortably into either category;

- (d) the boundary between self-employment and paid employment, particularly with respect to working proprietors of incorporated enterprises and dependent workers who have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature;

- (e) applicability of the standards to informal employment situations, especially informal employees;

- (f) the identification of workers in various non-standard forms of employment such as casual, short-term, temporary and seasonal employees, and workers on zero-hours contracts;

- (g) the need for guidelines on data collection, questionnaire design, derivation and adaptation of the standards for national use;

- (h) the identification and statistical treatment of various specific types of worker including:

- apprentices, trainees and interns;

- entrepreneurs;

- wage and salary earners;

- family workers;

- domestic workers;

- homeworkers and outworkers;

- members of producers’ cooperatives;

- workers with multi-party employment arrangements, including those engaged

- by labour hire agencies or temporary employment agencies.

36. It would be difficult, within a single classificatory framework, to provide a set of mutually exclusive categories that would allow the identification of all of these groups and satisfy the numerous and very different purposes for which statistics on the employment relationship are required. It was agreed therefore to develop a set of proposals to replace ICSE-93 with a suite of standards for statistics on the relationships between workers and the economic unit for which they work, rather than incorporating a number of overlapping concepts and characteristics in a single complex classification.

Outline of the proposed new standards

37. The draft resolution concerning statistics on work relationships aims to promote the coherence and integration of statistics from different sources on multiple characteristics of work relationships, by providing:

- (a) an overarching conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships which defines the key concepts, variables and classification schemes included in the new standards for statistics on work relationships;

- (b) a revised International Classification of Status in Employment (to be designated ICSE-18);

- (c) an International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW-18) as a reference classification covering all forms of work;

- (d) a set of cross-cutting variables and categories that support the derivation and analysis of the status at work categories;

- (e) operational concepts, definitions and guidelines for the collection and compilation of statistics on status in employment and the cross-cutting variables.

38. The revised ICSE-18 comprises ten categories which may be aggregated according to two alternative classification structures. The first structure, based on the type of authority that the worker exercises over the economic unit for which he/she works, provides categories at its top level for “dependent” and “independent workers”. The second structure, based on the type of economic risk to which the worker is exposed, creates a dichotomy between “workers in employment for pay” and “workers in employment for profit”. This is similar to the traditional distinction between paid employment and self-employment.

39. The ICSE-93 categories of employers, own-account workers, contributing family workers and employees have been retained in the proposed ICSE-18. The aggregate categories in the ICSE-18 structure based on the type of authority are therefore quite similar to the ICSE93 categories. In addition, the revised ICSE includes four subcategories of employees, separate categories for owner-operators of corporations and a separate category for dependent contractors.

40. A separate category for workers in producers’ cooperatives has not been retained in ICSE18, as the number of persons reported as employed in this ICSE-93 category is very small in almost all countries. Many countries do not use this category in their national statistics.4

41. The proposed new category of “dependent contractors” refers to “workers who have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature to provide goods or services for or on behalf of another economic unit, are not employees of that economic unit, but are dependent on that unit for organization and execution of the work or for access to the market.”. They may either provide labour to others while having contractual arrangements similar to self-employment or else they own and operate a business without employees but do not have full control or authority over their work. This new category is needed to provide information on the group of workers frequently referred to as the “dependent selfemployed”, which was one of the most important objectives of the revision work.

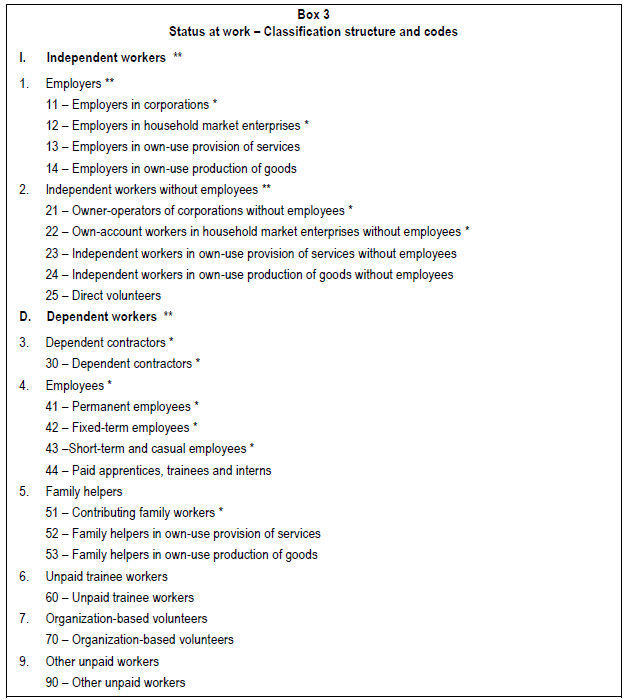

42. The proposed ICSaW-18 is an extension of the classification of Status in Employment to cover all forms of work, including own-use production work, volunteer work and unpaid trainee work, as well as employment. Its purpose is to allow the production of conceptually consistent statistics on different populations and from different sources, rather than to be used in its entirety for the compilation of statistics from any particular survey. The categories in ICSaW are defined in such a way as to allow the provision of separate statistics on activities within and beyond the SNA production boundary.

43. The classifications according to status are complemented by a set of cross-cutting variables and categories which provide definitions and categories for types of arrangement that cut across several status categories. Many of these variables are regularly included in most Labour Force Surveys but are not covered by internationally agreed statistical standards. The proposals therefore seek not only to provide more relevant and detailed statistics on status in employment but also to promote greater harmonization, coherence and international comparability of statistics on various aspects of the contractual and other conditions in which work is performed.

Main differences between the proposed new standards and ICSE-93

44. The proposed new standards have a wider scope than ICSE-93, since the overall framework can be applied to all forms of work defined in the 19th ICLS resolution I, whereas ICSE-93 is restricted to employment as defined by the 13th ICLS. Some of the proposed new classifications and variables apply to all forms of work whereas others are restricted to a single form or to certain forms of work.

45. While the proposed ICSaW includes categories relevant to all forms of work, the proposed ICSE-18 is applicable to employment as defined by the 19th ICLS. It is therefore narrower in scope than ICSE-93.

46. The ICSE-18 is generally more detailed than ICSE-93 and includes ten categories at its most detailed level, compared to the five in ICSE-93. Some of the concepts defined in ICSE-93 as “particular groups” for optional use at national level are covered by new categories in ICSE-18, including owner-operators of corporations, dependent contractors and subcategories of employee. Since members of producers’ cooperatives are no longer identified as a separate category in the revised ICSE, the owner-operators of enterprises that are members of producers’ cooperatives will generally be classified either as employers, or as independent workers without employees, as appropriate. The “crosscutting” variables and classification schemes proposed in the new standards were not included in ICSE-93 but do reflect some of the ICSE-93 “particular groups”, or the statistical needs underlying them. More detailed information about the differences between ICSE-93 and ICSE-18 is provided in Chapter 3.

Guidelines for data collection and measurement approach

47. A major criticism of ICSE-93 is the absence of guidance on methods and approaches to collect data on status in employment and on work relationships more generally. Reflecting this concern and to ensure the statistical feasibility of the proposals, data collection guidelines have been developed and tested (to the extent possible) in parallel with the conceptual development work. They will provide guidance on the collection of statistics on work relationships in Labour Force Surveys, as well as on the use of reduced sets of questions in statistical collections where the fully detailed categories are not collected. Such data collections could include household surveys, the population census, employer surveys and administrative collections.

48. The approach proposed for the collection of statistics on status in employment in household surveys builds on existing common practice by asking an initial question to allow respondents to self-identify based on the categories “self-employed”, “employee”, “family worker” and “trainee”. Depending on the response to the initial question, respondents are directed to different streams of questions to allow the identification of dependent contractors, classification to more detailed levels of status in employment and to verify the accuracy of the initial response. While this approach may increase respondent burden and the complexity of questionnaires, the importance of collecting information on status in employment with an adequate degree of precision is widely acknowledged. Reliance on self-identification alone is likely to result in significant levels of misclassification.5 Much of the information required is already commonly collected in Labour Force Surveys.

2. Conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships

49. The proposed conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships uses two aspects of the work relationship as criteria to differentiate categories of jobs and work activities according to status and to arrange them into aggregate groups. These are the type of authority that the worker is able to exercise over the economic unit for which the work is performed and the type of economic risk to which the worker is exposed.

50. The detailed categories in the revised classification of status in employment (ICSE-18) may be aggregated according to alternative hierarchies, one based on the type of authority and the other on the nature of the economic risk to which the worker is exposed. This allows the production of separate statistics on dependent and independent workers and on those employed for pay and for profit. This latter dichotomy is aligned with the current distinction between paid employment and self-employment. The new terminology more accurately reflects the reality of the situation, especially for dependent workers employed for profit.

51. The concepts used to define the classification of status in employment are also used to define the categories in the proposed ICSaW-18. The detailed categories in ICSE-18 are a subset of those included in ICSaW-18. These classifications by status are complemented by a set of standard cross-cutting variables and categories that provide more detail, allow the identification of specific groups of interest and reflect characteristics that are not covered in the classifications according to status.

Statistical units and work relationships

52. Statistics on the work relationship are concerned with: (a) the authority relationships between persons who work and the economic units in which or for which the work is performed; and (b) the contractual or other conditions in which the work is performed.

53. The concept of economic unit used in the framework is aligned with the institutional units defined in the 2008 SNA which distinguishes between:

- (a) market units (i.e. corporations, quasi-corporations and household unincorporated market enterprises);

- (b) non-market units (i.e. government and non-profit institutions serving households); and

- (c) households that produce goods or services for own final use (domestic households).

54. Since persons frequently perform work for more than one economic unit, and the nature of their work relationships may differ for each unit, statistics on work relationships refer primarily to characteristics of jobs or work activities in particular economic units.

Refinement of the definition of job

55. The 19th ICLS resolution I, paragraph 12(b) defines a job or work activity as a set of tasks and duties performed, or meant to be performed, by one person for a single economic unit and goes on to note that:

- (i ) The term job is used in reference to employment. Persons may have one or several jobs. Those in self-employment will have as many jobs as the economic units they own or co-own, irrespective of the number of clients served. In cases of multiple jobholding, the main job is that with the longest hours usually worked, as defined in the international statistical standards on working time.

- (ii) This statistical unit, when relating to own-use production work, unpaid trainee work, and volunteer work is referred to as work activity.

56. The draft 20th ICLS resolution concerning statistics on work relationships proposes to refine and clarify the definition of job or work activity (see Appendix, paragraph 8) by specifying that for those employed as dependent workers, the set of tasks should be considered to be performed for the economic unit on which the worker is dependent and that a separate job should be defined for each economic unit on which the worker is dependent. A vehicle driver, for example, who accesses clients using two different ride providing agencies (such as Uber and Lyft) will have two different jobs and may be a dependent worker in both jobs. This ensures that dependent workers employed for profit are not classified as independent if the work is performed for more than one entity. It also means that separate jobs are defined in cases where some activities are undertaken on a dependent basis, and others on an independent or freelance basis.

57. A further refinement ensures that separate work activities are defined when a person is engaged in both own-use production of goods and own-use provision of services in the same economic unit. This allows work activities within the SNA production boundary to be separately identified from those work activities that are outside the production boundary. This may also facilitate the production of statistics relevant to issues such as gender segregation in own-use production of goods and services. If a single work activity were defined for both the production of goods and the provision of services, three categories would be required in the classification of status at work, for those who produce services only, goods only, and both goods and services.

58. Non-standard employment arrangements commonly occur in jobs that are not a person’s main or even second job. The prevalence of these forms of employment may therefore be under-reported, since many household surveys measuring employment only cover a main job, or possibly main plus second job. The resolution therefore notes the importance of measuring work relationships in multiple jobs and work activities in order to measure the prevalence of non-standard employment. While this is recognized as being complex it is a broader challenge facing household surveys measuring labour and not limited to statistics on work relationships.

59. While the term “worker” is not formally defined in international standards for labour statistics, it may be used in a general sense to refer to any person who works. In the standards for statistics on work relationships it is mainly used to refer to the persons role in the context of a job or work activity in a particular economic unit. The same person may therefore be described as a dependent worker in one job or work activity and an independent worker in another.

Categorization based on authority and economic risk

60. This section describes the concepts of type of authority and type of economic risk, the relevance of these concepts to different types of jobs and work activity and the way they are used to create dichotomous categories of dependent and independent workers in the case of type of authority, and of workers employed for profit and employed for pay in the case of type of economic risk.

Type of authority

61. The type of authority exercised by the worker is defined in paragraph 11 of the draft resolution and is used to classify jobs and work activities as being independent or dependent and to arrange them into two broad groups: independent workers and dependent workers. Since workers within each of these broad categories may, in practice, have greater or lesser degrees of authority and dependence, there is to a certain extent a continuum between dependent and independent work.

62. Two aspects of dependence and authority are taken into consideration in the identification of dependent and independent workers: operational dependence and economic dependence. Operational dependence refers to whether the person has control over when and how the work is done, can make the most important decisions about the activities of the business, or is accountable to or supervised by another person or economic unit. Economic dependence refers to whether the worker or another person or economic unit controls access to the market, raw materials and capital items.

63. Independent workers control the activities of the economic units in which they work, either entirely independently or in partnership with others. They make the most important decisions about the activities of the economic unit and the organization of their work, are not supervised by other workers, nor are they dependent on a single other economic unit or person for access to the market, raw materials or capital items.

64. Dependent workers do not have complete authority or control over the economic unit in which or for which they work. They include employees, family helpers and dependent contractors.

Type of economic risk

65. Type of economic risk refers to the extent to which the worker may: (1) be exposed to the loss of financial or other resources in pursuance of the activity; and (2) experience unreliability of remuneration in cash or in kind as a result of the work performed, or receive no remuneration. In the case of workers employed for profit and owner-operators of corporations, the exposure to economic risk may result in financial loss but may also provide an enhanced opportunity to increase income and accumulate wealth.

66. The resolution provides information on the criteria that may be used for operational measurement of economic risk and on the aspects of the nature of the remuneration taken into consideration in order to differentiate workers employed for profit from workers employed for pay.

67. The concept of economic risk is of less relevance to the determination of specific groups of workers in forms of work other than employment. However, work activities in these other forms of work may also expose those performing these activities to varying degrees of economic risk.

Supporting concepts

68. Definitions of concepts that are used as part of the definition of categories and variables used in the framework are provided below. Many of these concepts are already defined in existing statistical standards such as the 2008 SNA, ISIC Rev.4 or the 19th ICLS standards. Where this is the case they are reproduced here for convenience.

Institutional and economic units

69. An institutional unit is defined for the purposes of economic statistics as an economic entity that is capable, in its own right, of owning assets, incurring liabilities and engaging in economic activities and transactions with other entities. It may own and exchange goods and assets, is legally responsible for the economic transactions that it carries out and may enter into legal contracts. An important attribute of the institutional unit is that a set of economic accounts exists or can be compiled for the unit. This set of accounts includes consolidated financial accounts and/or a balance sheet of assets and liabilities.

70. Institutional units include persons or groups of persons in the form of households and legal or social entities whose existence is recognized by law or society independently of the persons or other entities that may own or control them.6

71. The term “economic unit” is used in the draft resolution to refer to institutional units as producers or consumers of goods and services, whether or not a set of accounts exists for the unit. More than one economic unit may be defined for each household.

Enterprise

72. An enterprise is defined in ISIC Rev.4 as an institutional unit in its capacity as a producer of goods and services. It is an economic transactor with autonomy in respect of financial and investment decision-making, as well as authority and responsibility for allocating resources for the production of goods and services. It may be engaged in one or more productive activities.

73. An enterprise may be a corporation (or quasi-corporation), a non-profit institution or an unincorporated enterprise. Corporate enterprises and non-profit institutions are complete institutional units. On the other hand, the term “unincorporated enterprise” refers to an institutional unit – a household or government unit – only in its capacity as a producer of goods and services.

Corporation

74. The 2008 SNA treats all entities as corporations if they are:

- (a) capable of generating a profit or other financial gain for their owners;

- (b) recognized at law as separate legal entities from their owners who enjoy limited liability;

- (c) set up for purposes of engaging in market production.

75. As well as legally constituted corporations, the term “corporations” is used in the SNA to include cooperatives, limited liability partnerships, notional resident units and quasicorporations. The concept of “corporation” used in statistics on work relationships is more restricted than that used for national accounts purposes. It includes legally constituted corporations, cooperatives and limited liability corporations but excludes quasicorporations owned by households.

Quasi-corporation

76. According to the 2008 SNA a quasi-corporation is:

- (a) either an unincorporated enterprise owned by a resident institutional unit that has sufficient information to compile a complete set of accounts and is operated as if it were a separate corporation and whose de facto relationship to its owner is that of a corporation to its shareholders; or

- (b) an unincorporated enterprise owned by a non-resident institutional unit that is deemed to be a resident institutional unit because it engages in a significant amount of production in the economic territory over a long or indefinite period of time.

77. Three main kinds of quasi-corporation are recognized in the 2008 SNA:

- (a) unincorporated enterprises owned by government units that are engaged in market production and that are operated in a similar way to publicly owned corporations;

- (b) unincorporated enterprises, including unincorporated partnerships or trusts, owned by households that are operated as if they were privately owned corporations;

- (c) unincorporated enterprises that belong to institutional units resident abroad, referred to as “branches”.

78. For the purposes of labour statistics and the classification of the status in employment of the person in a particular job, however, the availability of a complete set of accounts is not a key defining criterion. Owner-operators of household market enterprises should be treated consistently regardless of the availability of a complete set of accounts. They are not separate legal entities from the enterprises in which they work and are exposed to similar economic risks as those who operate enterprises without providing a complete set of accounts. Accordingly, quasi-corporations owned by households (type b above) are not considered as corporations in the standards for statistics on work relationships

Household

79. The concept of household used in these standards is aligned with the definition used for the purposes of the 2008 SNA. A household is defined as a group of persons who share the same living accommodation, who pool some, or all, of their income and wealth and who consume certain types of goods and services collectively, mainly housing and food.7

80. Domestic staff who live on the same premises as their employer do not form part of their employer’s household even though they may be provided with accommodation and meals as remuneration in kind. Paid domestic employees have no claim upon the collective resources of their employers’ households and the accommodation and food they consume are not included with their employer’s consumption. They should therefore be treated as belonging to separate households from their employers.8

Household market enterprises

81. Household market enterprises are unincorporated enterprises owned by households that mainly produce goods or services for sale or barter on the market. They can be engaged in virtually any kind of productive activity: agriculture; mining; manufacturing; construction; retail distribution; or the production of other kinds of services. They can range from single persons working as street traders or shoe cleaners with virtually no capital or premises of their own through to large manufacturing, construction or service enterprises with many employees.9

Entrepreneurs

82. Entrepreneurs are persons who own and control an enterprise and seek to generate value through the creation of economic activity by identifying and exploiting new products, processes or markets. In doing so, they create employment for themselves and potentially for others. This definition is aligned with that included in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (draft) guidelines on the use of statistical business registers for business demography and entrepreneurship statistics.

83. Those who work on a volunteer basis in non-profit institutions which they control and operate, as well as some workers in own-use production, may also be considered in some contexts as entrepreneurs, because they may create both unpaid work and paid employment for others. Since the main statistical interest in identifying entrepreneurs relates to those who create employment for themselves and for others, this is the concept proposed for the statistical measurement of entrepreneurs.

84. The category of “independent workers” in the classification of status in employment provides the best starting point for the identification and compilation of statistics on entrepreneurs, as it includes own-account workers and employers in both incorporated and unincorporated enterprises This approach appropriately excludes employees, dependent contractors and contributing family workers from the measurement of entrepreneurs.

85. The draft resolution notes that additional information relevant to the national context is needed to provide complete statistics on entrepreneurship. In some contexts, there is interest in “entrepreneurship” in the sense of starting a new business. The time when the job started is useful as a supplementary variable in this respect. Statistics on the number of employees are also relevant to the compilation of statistics on entrepreneurs.

3. Status in employment

86. The proposal for a revised ICSE-18 classifies jobs in employment for pay or profit based on the type of authority the worker is able to exercise in the job and the type of economic risk to which the worker is exposed. The ten detailed categories in ICSE-18 have the same definitions, scope and codes as the equivalent categories in the Classification of Status at Work. These categories are used as common building blocks to create two alternative classification hierarchies, one according to the type of authority the worker is able to exercise in relation to the work performed and the other according to the type of economic risk to which the worker is exposed.

87. The draft resolution notes that the two hierarchies for status in employment based on economic risk and on authority should have equal priority in the compilation of statistical outputs. Statistics from Labour Force Surveys and other relevant sources should be compiled on a regular basis according to both hierarchies. The hierarchy used will depend on the analytical purpose of the output in question.

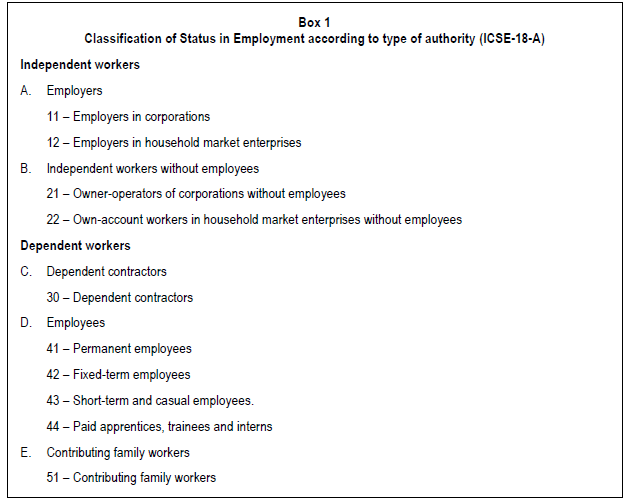

88. The hierarchy based on the type of authority can be used to produce statistics on two broad groups of workers in employment: independent workers and dependent workers. This hierarchy is referred to as the ICSE-18 according to type of authority and abbreviated to ICSE-18-A. It is suitable for various types of labour market analysis, including analysis of the impact of economic cycles on the labour market, analysis of government policies related to employment creation and regulation, and as a starting point for the identification of entrepreneurs.

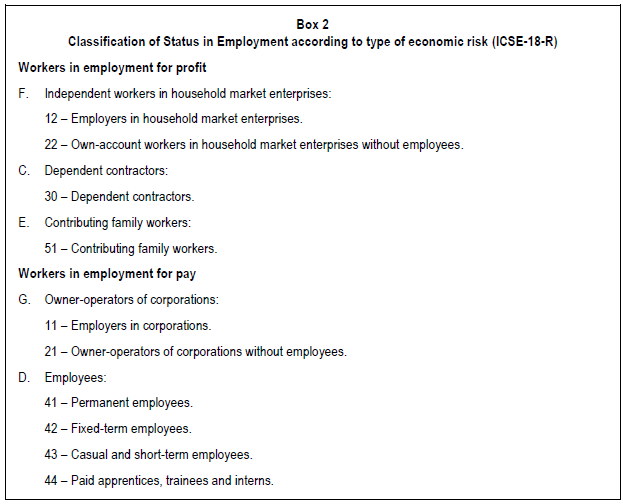

89. The second hierarchy, based on the type of economic risk, produces the dichotomy between workers in employment for profit and workers in employment for pay. This is analogous to the traditional distinction between self-employment and paid employment. This hierarchy is referred to as the ICSE-18 according to type of economic risk, and abbreviated to ICSE-18-R. It is suitable for the provision of data for national accounts, for the identification of wage employment and its distribution, and for the production and analysis of statistics on wages, earnings and labour costs.

90. The detailed categories in the ICSE-18 classification structures are assigned the same twodigit numerical code in each classification, the first digit being the same as the code for the aggregate categories in ICSaW-18. The aggregate categories in the two ICSE-18 hierarchies are assigned a single-character unique alphabetic code, so as to avoid confusion with the equivalent categories in ICSaW-18 that have a broader scope than in ICSE-18.

Summary of differences between ICSE-93 and the proposed ICSE-18

91. Since the ICSE-18 is comprised of categories that relate to employment as defined by the 19th ICLS resolution I, it is narrower in scope than ICSE-93. Specifically, the 19th ICLS concept of employment excludes own-use production of goods, all categories of volunteer work, unpaid trainee work and compulsory unpaid work. Since the scope of ICSE-93 is based on the 13th ICLS concept of employment, it includes own-use production of goods, certain categories of volunteer work, unpaid trainee work and some types of compulsory unpaid work.

92. The ICSE-93 has a single hierarchical structure comprising five substantive categories that are aggregated according to a combination of the type of economic risk and the type of authority to form the dichotomous categories of “paid employment jobs” and “selfemployment jobs”. The ICSE-18 has ten detailed categories that may be aggregated either according to type of economic risk or type of authority to form two alternative hierarchies.

93. The additional detailed groups in ICSE-18 relate to some of the concepts defined in paragraph 14 of the 15th ICLS resolution concerning the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-93) which outlines the “possible statistical treatment of particular groups of workers”. These include the new categories in ICSE-18 which allow for the separate identification of owner-managers of corporations, dependent contractors and subcategories of employee. Some other “particular groups”, or the statistical needs underlying them, are reflected in the various cross-cutting variables included in the proposed standards.

94. The ICSE-18 group “owner-operators of corporations” is equivalent to the group “ownermanagers of incorporated enterprises” defined in ICSE-93 as a “particular group” which countries may need or be able to distinguish for specific descriptive or analytical purposes. The ICSE-93 notes that different users of labour market, social and economic statistics may have different views on whether these workers are best classified as in paid employment or as in self-employment. The ICSE-18 classifies them as independent workers in the classification by type of authority and as workers in employment for pay in the classification according to type of economic risk. The ICSE-18 also provides further disaggregation of owner-operators of corporations through separate detailed groups for those with employees and those without employees. Separate identification of these workers is important for statistics on employment by institutional sector, wages and income, labour market characteristics and workplace relations, as well as for input to the national accounts.

95. The new category for dependent contractors allows the identification of workers who are employed for profit but do not have full control over the activities of the economic unit for which they work. This category replaces the concept of “contractors” specified as a “particular group” in the ICSE-93 resolution. Paragraph 14![]() of this resolution defines contractors as workers who:

of this resolution defines contractors as workers who:

- (a) have registered with the tax authorities (and/or other relevant bodies) as a separate business unit responsible for the relevant forms of taxes, and/or who have made arrangements so that their employing organization is not responsible for relevant social security payments, and/or the contractual relationship is not subject to national labour legislation applicable to, for example, “regular employees” but who;

- (b) hold explicit or implicit contracts which correspond to those of “paid employment”.

96. The ICSE-93 resolution notes that these workers may be classified as in a “selfemployment job”, or as in a “paid employment job” depending on national circumstances. In ICSE-18, dependent contractors are classified as “dependent workers” in the classification according to type of authority and as “workers in employment for profit” in the classification according to type of economic risk. The ICSE-18 concept of dependent contractors is also somewhat broader than the ICSE-93 concept of contractors, in the sense that there is no requirement for registration as a separate business, for exemption from employer responsibilities for social security payments, or to make arrangements such that the contractual relationship is not subject to national labour law. Nor is there any requirement for contracts which “correspond to those of paid employment”.

97. In some cases, the statistical treatment of the “particular groups” defined in paragraph 14 of the 15th ICLS resolution is clarified by the draft 20th ICLS resolution, even though these categories are not separately identified or replaced by the new proposed standards. For example, franchisees who engage employees or who operate incorporated enterprises, will be classified as independent workers. If they have no employees however, and their business is not incorporated, they may be classified as dependent contractors. Sharecroppers, as defined in ICSE-93, would generally be classified as dependent contractors if they have no employees. Work gang (crew) members are covered by an inclusion statement in the ICSE-18 definition of employees.

98. Subcategories are provided for employees in order to provide more detailed information about the stability of employment relationships for these workers, to allow the identification of employees with non-standard employment arrangements, and to allow the identification of paid apprentices, trainees and interns.

99. In addition to the provision of more detailed groups, ICSE-18 also makes adjustments to the boundaries between certain categories. In ICSE-93, the distinction between employers and own-account worker is based on whether or not employees were engaged on a continuous or regular basis. In the draft 20th ICLS resolution this is clarified by removing the word “continuous” and noting that “on a regular basis” should be interpreted as having at least one employee during the reference period and at least two of the three weeks immediately preceding the reference period.

100. The category of contributing family workers has been extended in ICSE-18 to include workers who help family members in a job in which the assisted family or household member is an employee or dependent contractor, in addition to those who assist in an enterprise operated by a family member.

Employment in cooperatives

101. The ICSE-93 category Members of producers’ cooperatives is not used by most countries, and is not identified as a separate category in the proposed new standards. The number of persons employed in this category is very small in almost all countries. This gives a misleading impression of the impact of cooperatives on employment, however, as employment in other types of cooperatives and of persons who are not members of the cooperative is not covered. In addition, since members of producer cooperatives are generally enterprises, rather than persons, the workers who own and operate these enterprises may frequently be classified in ICSE-93 as own-account workers or employers in their own enterprises, rather than as workers in the cooperative. In ICSE-18 they are classified as independent workers.

102. Members of worker cooperatives (worker members), on the other hand, are individuals who work in a cooperative which they jointly own. Like employee shareholders in other types of corporations, they have a vote on key decisions and on election of the board. Voting is based on membership (one member one vote) rather than on the share of capital, however. Since they do not have the same degree of control over the business as a majority shareholder they are classified in ICSE-18 as dependent workers. Classifying worker members of cooperatives as independent workers would also mean many of them might be classified as employers, since some worker cooperatives have employees who are not members. This could potentially result in misleading statistics on the number of employers.

103. If worker members of cooperatives are paid for time worked or for each task or piece of work done in the cooperative, they should be classified as employees of their own cooperative; if they are paid only in profit or surplus, or paid a fee per service, they should be classified as dependent contractors.

104. Further guidance on the treatment of employment in cooperatives is provided in the draft Guidelines for statistics of cooperatives to be presented for consideration and possible endorsement at the 20th ICLS.

Definitions and explanatory notes for categories in the two hierarchies of the International Classification of Status in Employment

105. Short definitions of each category included in ICSE-18 are provided in the draft resolution. The aim is to provide clarity on the conceptual boundaries between the categories and sufficient detail to support the development of operational methods for measurement, without however going into lengthy discussion on methods for measurement. To avoid repetition, the definitions of the detailed categories do not include information that is covered in the definitions of the relevant higher level categories. As a result, the detailed definitions cannot stand alone without making reference to the higher level category.

106. More detailed information on measurement and comprehensive stand-alone explanatory notes for each category will be included in the papers on guidelines for data collection and the conceptual framework for statistics on work relationships, to be presented as room documents during the 20th ICLS.

107. While all the categories are defined in the draft resolution, some additional information is necessary to properly understand the context of the definition and is provided below.

Independent workers

108. In ICSE-18-A, independent workers are disaggregated first according to whether or not they had one or more employees on a regular basis. Employers and independent workers without employees are then further disaggregated according to whether or not the economic unit they own and control is a corporation or a household market enterprise.

Employers

109. In ICSE-93, the distinction between employers and other independent workers is based on whether or not employees were engaged on a continuous or regular basis. This was not considered to be sufficiently precise for measurement on a consistent basis, did not necessarily reflect short-term changes in labour market conditions, and was not aligned with the reference period used for other labour market statistics. In the draft 20th ICLS resolution the definition of employer is clarified by a statement that “on a regular basis” should be interpreted as having at least one employee during the reference period and at least two of the three weeks immediately preceding the reference period.

110. There is not complete agreement on the definition of employers, however. Some labour statisticians would prefer to base the definition on the same short reference period that is used to determine Labour Force Status. This means that any worker who employed at least one person during the reference period as an employee, would be classified as an employer. It can be argued, however, that the socio-economic characteristics of those who only engage employees occasionally are more similar to those of independent workers without employees than to those who have employees on a regular basis. Since it is common for businesses in some countries to hire employees on a casual basis for just one day, there are concerns that changing the definition to a short reference period without further qualification could lead to a significant increase in the number of employers and more volatility in the statistics, especially for employers and own-account workers in agriculture.

111. If the definition of employer were based only on the reference period, the draft resolution may need to state that, if relevant in the national context, countries should separately identify employers who have employees on a regular basis from those who have employees only on an occasional basis along the following lines:

- Employers own the economic unit in which they work and control its activities on their own account or in partnership with others, and in this capacity employ one or more persons (including temporarily absent employees but excluding themselves, their partners and family helpers) to work as an employee during the reference period.

- Employers include those who have employees on a regular basis and those who have employees only on an occasional basis. Employers who have employees on a regular basis are those who usually have at least one employee during the reference period and at least two of the three weeks immediately preceding the reference period. Statistics on employers may be compiled either for those who have employees on a regular basis, or for all employers. When statistics are collected for all employers, those employers who have employees on a regular basis should, where possible, be identified separately from those who have them only on an occasional basis.

Owner-operators of corporations

112. The draft resolution defines owner-operators of corporations as workers who hold a job in an incorporated enterprise in which they hold controlling ownership and have the authority to act on behalf of the enterprise. The term “incorporated enterprise” refers to enterprises that are constituted as separate legal entities from their owners.

113. The draft resolution provides examples of terms that are used to describe different types of incorporated enterprise (limited liability corporation, limited partnership). To identify owner-operators of corporations in surveys, however, it will be necessary to ask questions of those who say they operate a business using terms for the specific legal forms that exist in the country. While respondents who do not operate an incorporated enterprise may not be familiar with these terms, it is likely that those who do operate such businesses, as well as their proxy respondents, will be well aware of the legal form of their business.

114. In ICSE-18-R, owner-operators of corporations are further disaggregated according to whether or not the enterprise has one or more employees on a regular basis.

Dependent contractors

115. The need for information on the group of workers frequently referred to as the “dependent self-employed” has been a major challenge for many statistical agencies in both the developed and developing world. These are workers who have contractual arrangements of a commercial nature to provide goods or services for or on behalf of another economic unit, are not employees of that economic unit, but are dependent on that unit for organization and execution of the work or for access to the market. Since these jobs do not fit comfortably into any of the substantive categories in ICSE-93, they are frequently classified either as own-account workers or as employees, resulting in overestimation of one or the other of these groups (or of both). As a result, it is difficult to monitor structural change in this important form of employment, which is considered by many researchers to be growing. This also impacts on the monitoring of structural change among both employees and independent workers. The need to address this problem was among the most challenging but also most important objectives of the revision work.

116. The ILO report for discussion at the Meeting of Experts on Non-Standard Forms of Employment held in Geneva from 16 to 19 February 2015, described dependent selfemployment as a situation in which “workers perform services for a business under a civil or commercial contract but depend on one or a small number of clients for their income and receive direct instructions regarding how the work is to be done”. That Meeting of Experts noted that non-standard forms of employment included, among others, “disguised employment relationships” and “dependent self-employment”. The first of these refers to workers who provide their labour to others while having contractual arrangements that correspond to self-employment. The second refers to those who operate a business without employees but do not have full control or authority over their work.

117. Statistics are needed about both groups to inform policy concerns about the use of contractors, transfer of economic risk from employers to workers, access to social protection and trends in non-standard forms of employment. There is a need for objective information to assess the extent to which jobs in these categories provide flexibility for both workers and employers, provide opportunities for labour market participation, and to inform debate on labour market policies and regulation. While ideally the two groups should be separately identified rather than grouped together, this is difficult to achieve operationally. The concept of dependent contractors proposed in the draft resolution covers both of these groups and allows for the separate identification of the two subgroups if feasible and relevant in the national context.

118. The need to include a category for this group in the classifications according to status has been widely (although not universally) accepted by labour statisticians and was strongly supported during the regional consultations. It is recognized in many countries to be a statistically significant and growing group, although comprehensive statistics about them are rarely available. Since they are both dependent workers and employed for profit they are identified as a separate group at the second level of each hierarchy in ICSE-18. This is necessary to ensure their statistical visibility. Moreover, it would be inappropriate to represent them as a subset of employees in one classification hierarchy and as a subset of independent or own-account workers in the other.

119. The types of job that should be included are quite diverse in terms of the nature of the work performed and the nature of the worker’s dependence on another economic unit. In many cases they involve types of contractual arrangement that have been in existence and inconsistently classified for many years. Examples include hairdressers who rent a chair in a salon and whose access to clients is entirely dependent on the salon owner, waiters who are paid only through tips from clients, vehicle drivers who have a service contract with a transport company which organizes their work, home-based workers who are contracted to perform manufacturing tasks such as assembling garments, and consultants working for corporations or government agencies.

120. The group also includes the emerging group of workers in the so-called “gig-economy” who have been the subject of considerable recent attention in academic, political and media discourse. Examples include vehicle drivers providing rides or parcel delivery services and home-based workers performing information-processing services, where organization of the work or access to clients is typically mediated through an Internet application controlled by a third party.

121. Despite this diversity, what workers in this group have in common is that they do not control the economic unit for which the work is performed, while being exposed to the economic risk associated with employment for profit. The different criteria used to define and measure them need to allow identification of those cases which fall into this category and are of genuine policy interest, while avoiding the identification of workers that are genuinely employees, freelance contractors or running their own business. These criteria also need to take account of the diversity of the nature of their dependency. Different criteria may therefore be more or less relevant, depending on the context.

122. Much of the early statistical development work on the definition and measurement of dependent contractors focused on dependence on one or a small number of clients. This approach, however, potentially includes genuinely independent workers who may have only a small number of clients in a given period, while excluding workers who have multiple clients but whose access to the market or access to raw materials is controlled by another entity. The working group for the revision of the ICSE-93 proposed additional features which could be used to identify dependent contractors such as payment of social contributions, type of payment received, dependence on another entity for access to the market, control over the price of the goods produced or services provided and various forms of control over the work performed.

123. The relevant section of the draft resolution starts with a short introductory sentence explaining the concept of dependent contractors that should ideally be measured. It then provides a short definition of a more operational nature: “workers employed for profit, who are dependent on another entity that exercises explicit or implicit control over their productive activities and directly benefits from the work performed by them”. To clarify the scope of the category, it goes on to note that dependency may be of an operational or economic nature and that the worker may be dependent on units in all sectors of the economy. A list of characteristics that may be relevant for the identification of dependent contractors, provides further clarification on the scope of the group and may also assist in the development of operational criteria for measurement.

124. Exclusion statements are provided to ensure that workers who have a contract of employment or are paid for time worked are classified as employees, not as dependent contractors. Similarly, workers who operate an incorporated enterprise, or who employ others to work for them as employees are classified as independent workers, even if their businesses are dependent on another enterprise. This establishes clear boundaries between the categories and ensures that classification is based on the relationship between the worker and the economic unit for which the work is performed, rather than on relationships between enterprises. The engagement of employees and incorporation of the enterprise both imply a degree of authority and control over the operation of an enterprise.

125. Testing currently under way in several countries is focusing strongly on the development of methods to identify dependent contractors in statistical collections, especially in household surveys. In order to differentiate these workers from own-account workers it is necessary to establish whether or not a single separate economic unit has control over access to the market or operational authority over the work. To differentiate them from employees, it is necessary to determine whether those who are reported in household surveys as working for someone else are in fact employed for profit.

126. The proposed measurement approach being tested identifies dependent contractors according to two streams from traditional status in employment questions: those who say they work for someone else, and those who say they are self-employed. It is possible to consider the workers identified by these two streams as if they were conceptually separate groups. Since this distinction is based on the perception of survey respondents, rather than on objective criteria, however, it does not provide a reliable distinction between the two groups of workers with disguised employment relationships and the dependent selfemployed. The draft resolution therefore proposes a single category of dependent contractors but notes that two subgroups of dependent contractors may be identified if information is available on the nature of the financial or material resources committed by the worker. More experience is required, however, before definitive guidance on measurement of dependent contractors can be provided.

Employees

127. The draft resolution defines employees as workers employed for pay, in a formal or informal business, who do not hold controlling ownership of the economic unit in which they are employed. The second part of this definition differentiates employees from owneroperators of corporations who may receive a wage or salary from the corporation that they own and operate. The four subcategories of employees allow permanent employees to be separately identified from fixed-term employees and from short-term and casual employees. Employment in this latter category may provide flexibility for workers who need to balance employment with family responsibilities, education, or other forms of work but may also entail insecurity of income and employment.

128. Permanent, fixed-term, short-term and casual employees are differentiated from each other based on three criteria:

- whether there is a specified date or event on which the employment will be terminated;

- the expected duration of the employment; and

- whether the employer agrees to provide work and pay for a specified number of hours in a set period and the worker agrees to work for at least the specified number of hours (contractual hours).

129. A boundary of three months is proposed to distinguish fixed-term from short-term employees. This reflects the thresholds of two or three months used in a number of countries to identify short-term employment for migrant workers. A duration of three months may also ensure the group is large enough to measure in typical household surveys.

130. The category of short-term and casual employees includes two very distinct groups: shortterm employees and casual or intermittent employees. In the case of short-term employees, the employment is by definition of a time-limited nature but provides a stable number of hours of work and income during that short period. Casual or intermittent employment may sometimes be of an ongoing nature, however, while providing no guarantee of employment for a certain number of hours. The resolution notes, therefore, that these two groups may be separately identified if relevant in national circumstances and provides a definition of each group.